8 practical things to consider before selling eggs for profit

If you have too many fresh eggs to eat yourself, selling them seems like a good idea. But making it profitable takes good management, and often a lot of paperwork.

Words: Sue Clarke

TV One’s show Fresh Eggs begins with an old-timer sneering a backhanded welcome to a new lifestyle block couple.

“Fresh eggs. It’s what we call you lifestyle blockers. First thing you do is put out a sign: fresh eggs.”

It’s true that those new to blocks are often surprised at what three layer hens can produce, around 18-20 eggs a week. All those eggs might inspire you to consider running a small-scale poultry business. But if you want to make a profit from selling fresh eggs, there’s a lot to think about.

THE ECONOMICS OF EGG PRODUCTION

The commercial poultry industry is incredibly efficient and runs on tight margins. A farmer’s advantage is economies of scale, with farms supporting hundreds of thousands of birds.

Small farms can struggle to be profitable, even with the marketing advantage of a local, organic, free-range niche.

The following will help you decide whether a poultry business may be feasible for your situation.

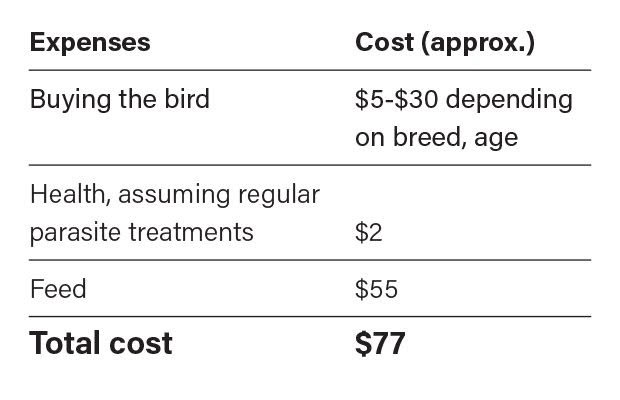

Costs

The biggest cost to consider is feed. A hen needs to eat every day of the year, even when she is not laying. Assuming you are running a 2kg commercial hybrid hen, the numbers look like this:

120g feed per day x 365 days = 44kg feed per hen, per year (approximately)

If you buy 20kg bags at $1.24 per kg ($24.80 per bag), that’s a yearly feed cost for one hen of around $55.

Commercial hybrids in peak condition can lay well over 300 eggs a year, but if we assume you get 300 eggs per year, that’s a feed cost of 18 cents per egg.

But there are other costs, including:

■ the initial capital cost of coops/sheds, feeders, waterers, plus replacement costs;

■ health treatments;

■ your time.

The cost of buying your first birds will vary, depending on what you choose to run. Commercial point-of-lay pullets can cost $20 each; heritage birds can be a lot more.

This is a basic outline of the total running cost per bird for 12 months.

Income

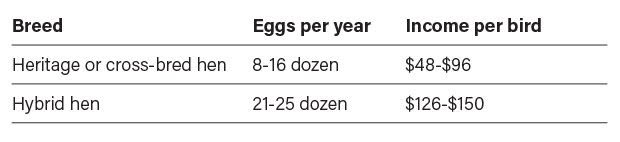

Poultry are seasonal layers. Heritage breeds in their first season, hatched in July-August, can lay 100-200 eggs per year. Commercial hybrids can lay 250-300 eggs. If you sell your eggs for $6 a dozen:

Profit

The problem with heritage birds is it can be difficult to make a profit. Take away the running costs ($77 per hen), and even if you can get peak egg production, you’re looking at:

Heritage/crossbred = -$29 loss – $19 profit

Commercial hybrids = $49 – $73 profit

These calculations assume your birds are always healthy and laying consistently, with no downtime for moulting or broodiness. It also assumes there is no feed wastage.

Sue’s tip: keep accurate records of daily egg production, feed use, and other costs

FIND YOUR MARKET

It’s important to know where you will sell your eggs before you start. When you have eggs, it’s likely other small flock owners will too, so will there be enough customers?

The problem is that hens are seasonal layers:

July-August: laying begins

November-December: laying may slow, or stop (eg, due to broodiness)

February-March: laying may continue, or start up again

March-June: laying stops as birds moult

If you want to be a small commercial venture with 100+ laying hens and supply eggs to large customers like cafés and restaurants, you’ll need a year-round supply of eggs. The only way to achieve this is by running multiple flocks of different ages, with young hens (aged 18-20 weeks) starting to lay every four months, for continuity of supply. You’ll also have older birds to dispose of or sell on.

This system will only be possible if you’re using commercial hybrids which are bred all year-round. They are also the most likely (if adequately housed, fed, and healthy) to keep laying through winter. You may need to provide artificial lighting during winter to create the 16-hour day-length which keeps birds laying.

Egg-laying is stimulated by hormones that are triggered by daylight length. Lighting can also encourage winter egg production from some of the more prolific heritage breeds like New Hampshires and Leghorns.

8 things to consider before getting into poultry farming for profit

■ council bylaws

■ MPI regulations

■ breed and source of birds

■ housing

■ health and welfare

■ feed supply and cost

■ manure management

■ what to do with old birds

1. COUNCIL RULES AND REGULATIONS

If you live in an urban or semi-rural district, your local council will have a restriction on the numbers of poultry you can keep. It varies from 10 to 25, depending on the council, and usually, no roosters are allowed.

Check with your council on:

■ permitted number of laying hens;

■ how far coops and pens must be from a dwelling and boundaries.

If you are in a rural zone, there may be no council limits on numbers or placement of coops and runs. If you own more than 99 female poultry of any species (eg, hens, ducks, quails) of any age, another set of regulations comes into play: MPI.

2. MPI RULES AND REGULATIONS

The Animal Products Act 1999 (APA) requires that most ‘primary processors of eggs’ have a registered and independently verified risk management programme (RMP) before they can sell their eggs. This is managed by the Ministry of Primary Industries (MPI).

An RMP outlines the operating practices of your farm, such as how much space they have to roam, the feed supply, and how you manage sick birds. It also requires you to explain how you manage risks, including:

■ hazards to consumers, eg collection and storage of eggs to maintain quality;

■ hazards to animal health, where eggs are used for pet food or animal feed;

■ how you check eggs for cracks or internal defects in yolks or whites, eg shell cleanliness, candling;

■ risks from false or misleading labelling.

How using someone else’s egg boxes can get you into trouble

If you are planning to sell eggs to the public, whatever the size of your flock, do not sell them in reused packaging if:

■ the cartons are damaged or dirty;

■ it includes the name, logo, or any

other details that identify the original poultry business. You must cover their details, perhaps with your own label, or remove them. If it’s not possible to hide or remove their details, don’t use the box.

Read more: Understanding the labelling requirements for eggs and egg products

3. BREED AND SOURCE OF BIRDS

You may choose to sell eggs from the birds you already have. However, also consider the economics of buying in good quality, young laying hens.

Heritage breeds

Pros: look beautiful; helps rare breed poultry numbers; eggs are often different colours (depending on the breed).

Cons: far lower annual egg numbers than commercial hybrids; low fertility; you will have to breed the birds yourself or pay for someone else to do it; half the chicks that hatch will be male.

Where to find: talk to poultry clubs

A lot of heritage breeds in NZ are bred to meet poultry show standards. These place a lot of emphasis on the look of the bird, not on egg production or fertility. The result is many heritage breeds are poor egg producers and have very low fertility. It may be difficult to find a good heritage layer line, with high egg production and fertility.

- Heritage Barnvelders can be good layers

- A hybrid layer hen (Shaver or Hyline) can lay over 300 eggs a year

You will also need to raise, or pay someone to raise, your replacement birds. Statistically, half those birds will be male, and you or a rearer will need to feed them until they 6-10+ weeks old before you can work that out.

There are a lot of costs in raising chicks. You need to pay for the facilities to hatch eggs and raise chicks, and specialist chick feed. You need to manage the facilities carefully to keep them in good health. It takes a lot longer to raise heritage breeds, which mature much more slowly than hybrids.

If you get everything right, you will have hens that may produce 200-250 eggs a year. That may not be enough to be profitable. If you want to use heritage birds, talk to poultry clubs and find members who breed for high egg production. It may be difficult to find someone who has a lot of birds to sell at the right age (preferably 18-25 weeks).

Hybrids

Pros: high feed-efficiency (eating the minimum amount of feed for a maximum number of eggs); high egg production (300+ eggs a year); only females are sold; can be bought as day-old chicks or easily sourced from professional rearers, from 10-25 weeks.

Cons: limited productive lifespan (18 months to three years); produce best on a commercial layer feed in perfect conditions.

Where to find chicks

Shaver Browns: Bromley Park

Hyline Browns: Golden Coast Hatchery

Where to find hybrid pullets: TradeMe, commercial rearing farms (if they have spare birds)

The best economic choices are the commercial hybrids, the Hyline Brown and Shaver Brown. These birds are the result of decades of breeding to create layer hens that produce high numbers of eggs (if fed and housed correctly) eating 120g a day each of good quality, nutritious, balanced feed.

You can buy them as day-old chicks, year-round, direct from the hatcheries. Shaver and Hyline pullets are also easy to find, sold by rearers nationwide.

The pros and cons of rescue hens

Commercial farms dispose of their Hyline or Shaver layers when the hens reach the end of their first year laying (at around 18 months of age). Some are rescued by groups around NZ. These hens can continue to produce a lot of eggs for the next year or so.

Once rescued, they will need to moult and then adjust to a life living outside, building up immunity to disease. Some won’t cope and will stop laying or die.

Hybrid birds are not bred for longevity, with an average lifespan of only 3-5 years. As they reach 3-4 years, they will lay fewer, larger eggs. However, it will still be at a rate far higher than most heritage breeds. It won’t be as economical to take on these birds, compared to hybrid pullets.

4. HOUSING

The size of your coop or shed will depend on the numbers you intend to keep. There are welfare codes which recommend minimum requirements for birds housed either fully indoors or with access to a free range: MPI Code of Welfare Layer hens, October 2018.

5. HEALTH AND WELFARE

Whether you have a few hens or a commercial flock of over 100, the responsibility for their continued health and egg production depends on good management.

You need at least one nest box for every 4-5 birds; the best nesting material is wood chips.

Prevention is the key, including:

■ maintaining a warm, airy (but not drafty), dry coop or shed;

■ cleaning it correctly and treating it for mites;

■ maintaining a good quality outdoor range, eg preventing mud, growing good quality plant cover;

■ feeding a good quality, balanced, nutritious layer feed;

■ controlling rodents and keeping birds safe from predators, eg cats, dogs, hawks, mustelids.

You need to have basic remedies on hand for internal and external parasites, vitamin and mineral supplements for birds that are ill. There should be separate facilities to quarantine new or sick birds.

Waterers should be off the ground, regularly cleaned and always filled with fresh water.

Being familiar with symptoms of common diseases is important. Have a budget so you can pay for diagnosis and treatment if you have a severe disease outbreak. Find a farm vet with poultry knowledge before you need them. Know where to find the closest avian vet.

You need to be capable of euthanising birds or have someone on call to do it for you, quickly and humanely.

6. FOOD SUPPLY AND COST

Feed is the most significant ongoing cost for any poultry farmer. Cheap feed is usually lower in protein. Hybrid layer hens won’t lay as well on this feed. They need around 120g of a balanced, nutritious feed with a protein content of 16.5-17 percent.

Any greens your hens eat while free-ranging is not going to provide this protein content. Feed pellets or mash in the morning, so birds get their daily protein, vitamin and mineral ration ahead of any low-nutrition vegetation. If you want to feed them again in the afternoon, give them a scratch feed (eg, wheat, maize) of 10g per bird.

Hens love to forage, but it’s important that they eat a good quality, balanced, nutritious layer feed first.

Larger heritage breeds will consume at least 150g of feed per day. However, they can still produce well on a lower protein feed (14-16 percent). A good commercial layer feed contains the ideal calcium level. However, some birds have a higher requirement for calcium. Have dishes of oyster shell grit, limestone chips or crushed dried eggshell available. Do not mix this into the main feed as you can over-dose those who

don’t require it.

Feed cost will vary around the country and by supplier. It’s important to check what feeds are closest to you (transport is a big expense) and the price. If you can buy and store feed in bulk, it will be cheaper.

However, you don’t want to store more than 6-8 weeks of feed, to maintain quality. Feed needs to be stored in a dry place, secure from rodents and wild birds. Old chest freezers or steel storage cupboards or bins are good options; rats can chew through even thick plastic and concrete.

If you run a large number of birds, you may want to consider a silo.

7. MANURE MANAGEMENT

Poultry produce a lot of manure. You can use it to create a valuable asset for your garden, your block, and as a fertiliser-compost you can sell.

The deep litter method is one of the best manure management techniques:

■ an initial 10cm+ thick layer of wood shavings;

■ a dry environment;

■ add to it regularly;

■ use a fork to aerate it periodically and/or spread a scratch feed so birds turn it over.

If you manage it well, the litter will stay smell-free and a pleasant consistency for up to a year, breaking down into good quality compost.

8. DISPOSAL OF BIRDS

Birds will eventually stop laying, or they may die prematurely. Commercial farmers budget on losing around 4 percent of birds per laying cycle (hens aged 18 weeks to approximately 18 months). A study of free-range commercial farms found the median death rate was around 7 percent, but one farm managed to keep to just 1.8 percent.

You may choose to keep old, non-layers until they die of natural causes, rehome them, or euthanise them once they finish laying. You need to plan how you want to dispose of the bodies. Burial is one option; hot composting is another.

If you choose to euthanise birds, the meat can be used for stock, casseroles or pet food. You may get enough meat off a heritage layer hen to make the time spent processing it worthwhile. However, the amount of meat on a commercial hybrid is very low, at best 200-300g and not worth the effort

3 WAYS TO AVOID AN RMP

You don’t need a risk management programme if you:

■ produce eggs for sale for human or animal consumption from 100 female birds or fewer (this includes all species that layeggs for human consumption,eg hens, ducks, quail);

■ sell all your eggs (human or animal consumption) direct to the consumer or end-user, and;

■ do not sell any eggs to any person for further sale (eg, cafe, shop, or other third parties).

Eggs are a perishable food, so if you do require an RMP, checks will be made from time to time on sources, labelling and product suitability. You can be fined if you don’t comply.

If you are eligible for an exemption from an RMP, it is up to you to prove it to MPI. This can be done by:

■ having a regular physical count of female birds on your property;

■ keeping young, growing female birds in a separate area to your adult layers;

■ having something like a conspicuous notice at your gate and/or where you sell your eggs. It will notify customers that eggs are only for sale to the final consumer and are not allowed to be on-sold or used to make foods that are then sold.

What MPI has to say about selling eggs

“You will not always know what people use your eggs for, but if you’re selling to another business of any type, it is highly likely the (RMP) exemption will not apply.

“If you know that the purchaser on-sells the eggs or uses them to prepare food that is sold to someone else, then you cannot sell to that person and claim the exemption.”

“You must sell the eggs yourself. This is normally done at the laying farm, a farmers’ market, or by delivering the eggs yourself to the consumer. You cannot have someone else sell your eggs for you at a farmers’ markets (or any other places) and claim the exemption.

4 BASIC HOUSING REQUIREMENTS

A good poultry house should:

■ be of a suitable size that hens can remain inside on wet and windy days;

■ face away from the predominant rain and wind direction;

■ be shaded from direct sunlight;

■ provide a warm habitat during periods of cold weather by preventing drafts and using insulation in walls. If possible, the roof should be insulated too. This prevents condensation from dripping down onto roosting birds and wetting the floor during winter.

Night time temperatures in winter in most areas of NZ sit just above freezing. Insulation to keep a coop or shed warm, without restricting air flow, is good for hens’ health, but also saves you money. A hen that needs to warm itself up will use more energy, and so will eat more than its minimum ration. The digestion process also helps to raise the temperature of the bird. Both increase your feed costs.

The floor material should be easy to clean, concrete if possible. The best covering is a clean, dry layer of litter, at least 10cm deep, so birds can scratch and dustbathe.

You need at least one nest box for every 4-5 birds; the best nesting material is wood chips.

Wood shavings are best, followed by bark chips, pine needles, and straw. Hay is not recommended as it doesn’t absorb moisture, leading to fungal spore growth which can cause respiratory diseases. Fungi can also penetrate shell membranes when the eggs are freshly laid and wet, contaminating them.

You need at least one nest box for every 4-5 hens, lined with a thick, clean layer of wood shavings. Eggs should be collected frequently, preferably twice a day.

Feed and water containers should be off the ground. This way, birds don’t have to lean down to eat and drink, a common cause of spilled feed and water. It also stops floor litter being scratched into the feed.

Commercial hybrids should have feed available 24-7 as they have small appetites. A treadle-type feeder is a good option, as it helps to prevent wild birds and rodents from stealing feed. If you are going to have large numbers of hens, you may find it economical to invest in a specialist feeding system.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.