6 ways to work out if your hens are laying

If you’re not getting all the eggs you expect, Sue Clarke explains how to work out who’s laying, who’s about to, and who’s cruising.

Words: Sue Clarke

Your best hens are laying an egg a day. Your new pullets may be due to start laying their first eggs any day. But which day? And are the old girls laying, or have they started their retirement?

There are a few useful signs that show if a hen is laying, about to, or not. You want to see a few of the following signs.

1. The feathers

PULLETS (aged 0-18+ weeks)

A pullet moults three times before finally growing her adult plumage. The timing varies depending on breed, but generally, chicks lose their down during weeks 1-6. They then partially moult feathers at 7-9 weeks, 12-16 weeks, and 20-22 weeks.

If you open the wing of a pullet aged 12-14 weeks old, you’ll see the quills (or growing feathers) are quite pointed. They only get their round-ended adult wing feathers in the final moult, along with much stiffer tail feathers.

Feather loss begins on the head and neck, then the saddle, breast, and body. The wings are last, and their progression gives you useful clues as to when a pullet will start to lay.

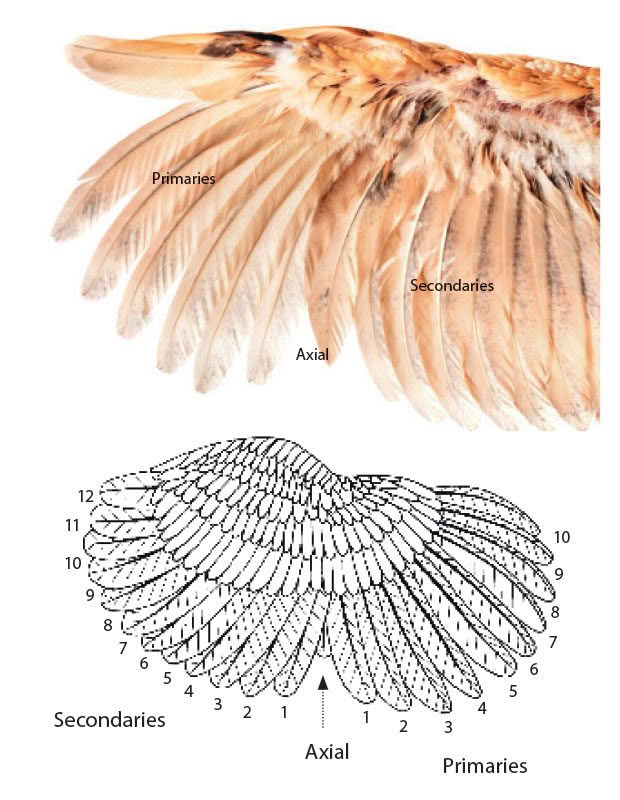

The primaries: on the outer part of the wing. Start falling from the centre, drop in order from 1-10.

The secondaries: these sit underneath a folded wing, and fall out in a random order, shortly after the first primaries

are lost.

The axials: shorter feathers in the centre (technically, they’re secondaries), which fall last. It takes around six weeks from the time a quill emerges from the skin, pushing the old feather out, to the time it’s fully developed. It gets to the 75% mark in three weeks.

You can use the process of old to new wing feathers to estimate when a pullet will lay:

– 4-5 weeks from when the wing feathers start to regrow;

– around one week when the last three primary feathers (feathers 8, 9, 10, above) are close to their final adult size.

The stiff white quills are a sign this hen still has a few weeks before she’s laying again.

DELAYS

Stress can delay how fast the feathers develop and the onset of laying in a pullet.

Stressors include:

• moving from one farm to another;

• moving from one coop to another;

• a change of feed;

• a change of season, especially to cold winter nights and lower hours of sunlight.

How quickly growth resumes depends on the bird, but it may take a week or more.

ADULTS

An adult hen, depending on age and breed, will start moulting as early as January (when daylight hours start falling), or as late as April.

It takes a chicken at least eight weeks to regrow their feathers, and it’s quite a strain on the body, which is why almost all hens stop laying. Some more persistent layers might keep going, often commercial hybrids.

The best layers tend to drop their feathers very quickly. The coop can look like a pillow exploded, and she’ll look like a pin cushion, covered in sharp quills.

The poorest layers may look quite normal throughout a moult, dropping feathers so slowly you don’t notice their loss or the growth of new ones.

As hens age, their moulting time gets longer and longer, until eventually they stop laying. ‘Old age’ in a hybrid can be just 3-4 years; some heritage birds may lay until they are much older.

2. Colour

THE HEAD

The intensity of colour in the skin of the face, comb, and wattles is a good indicator of whether hens or pullets are laying, or not. When reproductive hormones are strong, the skin in these areas will be bright cherry red with a waxy hue; if hormone levels are low, they’ll be a pale red or pink and look dry.

It’s more difficult to see the differences in dark-skinned birds such as Silkies, but you’ll still see a ‘glow’ to the skin of a bird that’s in lay compared to one that isn’t. It’s much easier in yellow-skinned breeds such as the Leghorn, Rhode Island Red, and Plymouth Rock. As a pullet grows, yellow pigment is deposited in the skin, beak, legs, and feet.

Pullet.

Once she starts laying eggs, the pigment slowly fades as the hen uses it to create yolk colour. If you can see yellow pigment in the eye ring, ear lobe, beak, and legs of a yellow-skinned breed, she’s not laying. One that is laying will have pink-red colouring to the face, and faded yellow legs.

When a yellow-skinned hen moults, she regains the yellow colour, then loses it again when she starts laying. The combs of broody and moulting hens will be very pale and shrivelled compared to those of a hen in full lay. A sick hen which stops laying will get paler in the comb, and it may also shrink or flop over.

THE VENT

A hen that’s laying will have moist-looking skin around the vent, flushed pink, and a wide entrance. A pullet or hen not in lay will have a tightly puckered vent, and the skin will be dry and pale.

PULLET VS ADULT HEN

Look at the colour of the young pullet (above) compared to the adult (below):

•the comb and wattle is much larger, redder, and waxy-looking in the adult, and more yellow in the pullet;

•the colour of the face, especially around the eye rim, which is a much darker red in the adult hen;

•the colour of the beak.

Adult hen.

Bonus tip: Skin colour will also tell you if a rooster is mating. Wrap him in a towel, tip him up, and check his vent. A rooster has a small, tight-looking vent compared to a laying hen, but if he’s regularly mating, the skin will be pink-red in colour. If he’s not, it will be very pale.

3. Activity

As hens or pullets near the time of laying their first egg, it’s common to see them moving in and out of nest boxes, investigating nooks and crannies such as barns or quiet spots in the garden, making a ‘chatty’ sound.

It’s important to ensure your nest boxes are her most attractive option, so she gets in the habit of laying eggs where it’s most convenient for you.

NEST BOXES SHOULD:

• be raised off the ground, from 10-50cm or so;

• have a ramp or perch in front;

• be the right size (30cm wide, 35cm deep, 30cm high);

• be dark – cover the top of the nests, and have them in the darkest part of the coop, facing away from windows or doors;

• have a ‘lip’ at the front, 10-15cm high, so hens can snuggle down behind it;

Dummy eggs or golf balls can help to entice a hen to lay in a nest box, as she’ll think other hens have laid there before her.

If she establishes a nest under a bush or in a haystack, it can be difficult to encourage her to lay in the coop unless you lock her in for a time (7 days or more) and force her to accept it.

Check nothing is making her uncomfortable, such as a red mite infestation, too much light, or too few nests for the number of hens.

WHAT A HEN WANTS

In the wild, a hen will leave the flock and go off into the undergrowth, often led by the rooster who will search out a spot for her. It’s why you sometimes see roosters in nest boxes, making a fuss.

HENS PREFER:

•nests low to the ground – the compromise is often 50cm, a workable height for a bending human;

•unpainted metallic or wooden nests over black, blue, green, yellow, or red;

•to snuggle down into a rounded nest with just their head peeking out;

•a flat (not rounded), wooden or metal (not plastic) perch, 8cm wide and 2cm deep.

•round nest openings, however it’s more difficult to build this shape than a square or rectangle. Large, round plastic buckets with a lip (eg, half a lid) across the front might meet with hen approval.

4. The bones

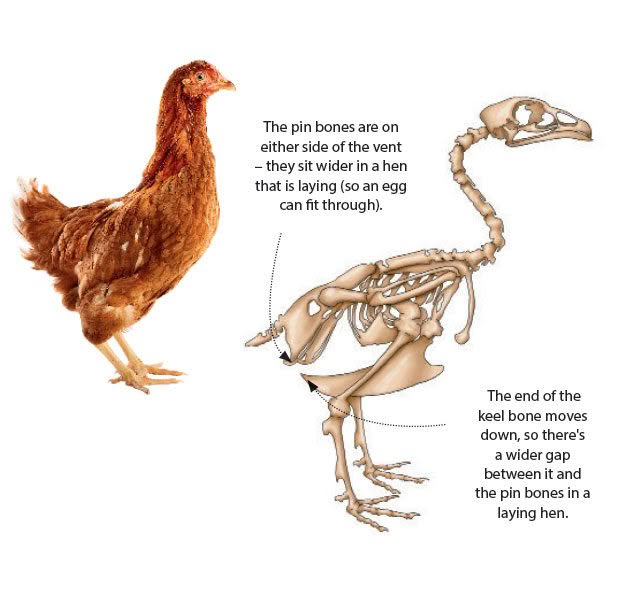

One of the best indicators of whether a hen is laying, or about to lay, is the placement of the bones around her vent and the rear of her abdomen.

As a pullet reaches laying age, oestrogen gradually builds up in the body. This initiates many physical changes, including:

• a widening of the gap between the pin bones, either side of the vent;

• a widening of the gap between the pin bones and the end of the keel;

• colour changes to the skin on the head and legs.

These changes take place in the month before a pullet begins to lay. Regularly check them, and you’ll feel the difference in the spacing of the bones. The widening of the bones won’t be quite as dramatic in an older hen who has been laying for a long time.

The gaps between the pin bones and the distance to the tip of the keel bone will be relative to the size of the bird. It will also vary depending on the size of your hand. What you’re checking for is the change in width.

As a pullet get close to laying, the gaps will steadily widen by maybe half a finger width (5mm) per week until she is ready to lay. By the time she’s laying, the gap between the pin bones will be about three fingers wide (4-6cm), and about a palm width (sideways, 7-9cm) between the tip of the keel and the pelvic bones.

Sue’s tip: If you’re still unsure, measure the width of the pin bones of a rooster – definitely not an egg layer – to get an idea of the kind of spacing you’d expect in a non-laying hen. His pin bones will only be about one finger width apart, and you’ll fit around two fingers held sideways between the tip of the keel and the pin bones above.

5. Time of year

The time of year birds hatch determines when they’ll start to lay. Chicks hatching late (mid-summer-late autumn) may not reach maturity until 4-10 weeks later than normal, depending on the breed. It means they miss out on the big burst of reproductive hormones generated by lengthening hours of daylight (from late June to late December).

Colder temperatures in autumn and winter, especially at night, also play a part. Poultry originate in the tropics and prefer warm weather. A hen uses up a lot of energy to stay warm through long, cold nights. This slows her weight gain, body development, and maturity, meaning she’ll start laying many weeks or months later than usual.

6. Breed

Pullets of different breeds start laying sooner than others.

LIGHT BREEDS

The first to mature and start laying if they have perfect conditions (increasing daylight hours, good body condition). You may see the first eggs when a bird is 16-18 weeks.

BANTAMS

They start to lay at 17-19 weeks. However, if they reach maturity in January (when daylight hours begin to fall), their hormone development slows, and they may not start laying until 20-22 weeks. If they hatch late in autumn, they mature even later, from 26 weeks onwards.

HEAVY BREEDS

These birds are the slowest to mature. They may not be ready to lay their first egg until 20-24 weeks. If they hatch after January (when daylight hours begin to fall), it can delay their maturity until 30-35 weeks.

IS YOUR BIRD LIGHT OR HEAVY?

Light breeds:

•mature weight around 2kg or so;

•usually of Mediterranean origin, includes commercial hybrids (Shaver, Hyline);

•tend to be highly strung and flighty compared to heavy breeds;

•tend to have a small appetite;

•lay more eggs than heavier breeds, usually (but not always) white or a lighter beige – the exception is the araucana (South American), which lays blue-green eggs.

Leghorns are light layers.

Heavy breeds:

•mature weight around 3kg or heavier;

•usually from the cooler regions of Europe and North America;

•tend to be more docile and quieter than light breeds;

•have a large appetite;

•lay brown eggs;

•lay far fewer eggs annually than a light breed.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.