6 trends to consider when planning a specialty timber crop

When planting a crop that’s ready to harvest in 30 years, it’s smart to look at long-term trends.

Words: Emma Rawson

Trend: naturally durable timber

There is a growing demand for naturally durable timber as consumers become more aware of toxic chemical preservative treatments such as chromated copper arsenate (CCA). It is commonly used to treat pine in New Zealand but is banned in several countries. There is also an increasing demand for traceability and sustainable forestry.

“Instead of choosing imported timbers, customers are looking for timber grown in New Zealand,” says specialist timber forester Gabrielle Walton.

Trend: sustainable forestry

Forestry methods are also becoming more relevant to consumers. Many people were horrified after a storm in 2018 left wood debris from forestry plantations covering the beach at Tolaga Bay. The cost of the clean-up was in the millions.

The event highlighted to people the environmental risks of clear felling, where an entire forest is cut down at the same time. The method leaves hillsides prone to erosion and can lead to water pollution.

A more sustainable way is ‘selective harvesting’ or ‘target diameter harvesting’, where only a small number of trees are felled when they reach a certain trunk width.

Wood debris from forestry that washed down into Tolaga Bay in 2018, costing millions to clean up.

“The idea is to maintain continuous-cover forestry, leaving the rest of the forest intact, when only the biggest trees are taken out,” says commercial forester Dean Satchell. “As a result, there is less erosion because there are still trees gripping the soil.”

Trend: the one billion dollar baby

The Government has set a goal of planting one billion trees over the next 10 years, roughly double the current planting rate.

Julie Collins, head of Te Uru Rakau (Forestry New Zealand), says the goals are to provide economic growth to the regions, improve water quality, and help NZ meet its climate change commitments.

She’d like to see block owners start planting small forests.

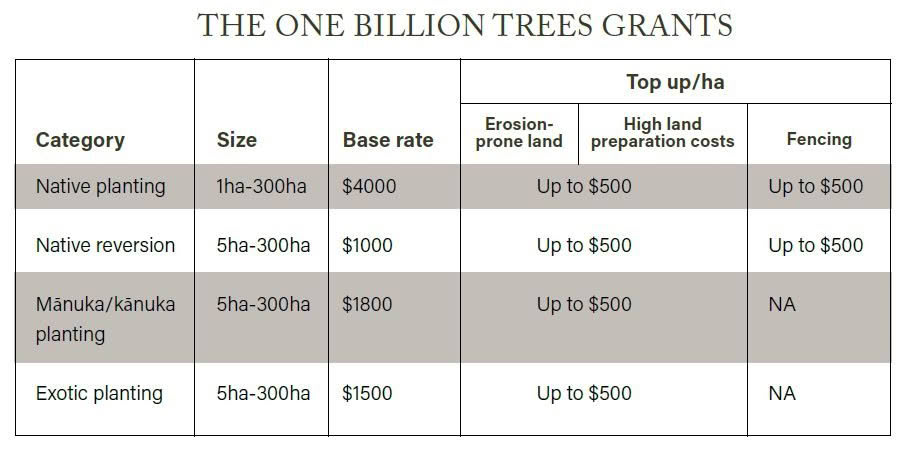

“We’re encouraging as many New Zealanders as possible to get involved in tree planting. To be eligible for a grant, you’ll need to meet a minimum planting area of between 1ha (2.5 acres) and 5ha (12.5 acres) depending on the species you are planting.”

There are some further criteria that landowners need to meet:

• the trees must be capable of reaching 5m in height at maturity in that location;

• the proposed planting density will probably be a minimum of 750 stems per hectare at establishment;

• the proposed project must be capable of reaching an average minimum canopy width at maturity of 30m (an exception to this is riparian planting which can be narrower).

Trend: carbon sequestration

The carbon sequestration rate – the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed by a tree – of certain species is something environmentally savvy consumers could become more aware of in the future, says Dean.

Generally, the denser the timber, the more carbon dioxide is absorbed. Forest Owners Association President Peter Weir says exotic plantation trees could be a ‘quick fix’ for New Zealand to reduce its net carbon emissions over the next couple of decades.

“It’s important to appreciate the large difference in sequestration rates between exotic plantation forests and native planting. Exotics are many times faster

at absorbing carbon.”

Trend: the environmental advantages of building with wood

Wood is the only construction material that absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during production. The more timber you use in a house, the more carbon dioxide you remove from the atmosphere.

One tonne of processed wood will have absorbed a net 1.7 tonnes of CO₂ from the atmosphere. Compare that with other building products:

• One tonne of concrete has released 159kg of CO₂ into the atmosphere;

• One tonne of steel has released 1.24 tonnes of CO₂ into the atmosphere;

• One tonne of aluminium has released 9.3 tonnes of CO₂ into the atmosphere.

Trend: the emissions trading scheme

This is a government incentive that rewards forest owners for the greenhouse gases absorbed by trees.

Participants in the emissions trading scheme (ETS) earn one carbon credit for every tonne of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere. Forest land planted post-1990 must be at least 1ha of forest species to qualify for the scheme.

Criteria includes:

• at least 30 percent of each ha of forest must be covered by tree canopy (known as tree crown cover);

• an average width of tree crown cover of at least 30m.

To be eligible, participants must register on the New Zealand Emissions Trading Register (www.eur.govt.nz) and use the online forest mapping tools to create a ‘Carbon Accounting Portfolio’. This is where growers can register deforestations or add additional ‘carbon accounting areas’ (forests).

An emissions return must be filed through an online portal at the end of five years. The current Mandatory Emissions Return Period is 2018-2022, and returns are due no later than June 2022.

If trees have grown, they will earn carbon credits. Forest farmers who have harvested trees may need to pay back the government.

The main unit of trade in the ETS is the New Zealand Unit (NZU) which represents one tonne of carbon dioxide.

The carbon emissions market is governed by complex monetary policy, complicated by the trade of international carbon credits. In 2013 the per-unit price was $2, but in 2019 it is up to $25 (there is currently a price ceiling on the NZU of $25).

NZUs can be sold through direct bilateral agreements with buyers, a broker, or an exchange. These transactions can be arranged by financial service providers in the private sector.

“A big change from our previous grant schemes is that you can now register forests planted under the One Billion Trees Fund with the ETS straight away, so long as the area is eligible (ie, it meets the post-1989 forest definition for the ETS),” says Julie Collins of Te Uru Rakau.

However, if you do receive a grant through the One Billion Trees Fund, it’s important to know it doesn’t guarantee that your trees can also be registered in the ETS, as its eligibility criteria is different.

NZ’s climate change policies are evolving to meet the emission reduction targets of the Paris Agreement. Many believe NZ’s current ETS scheme is too lenient on polluters/emitters. There is room for debate on the way carbon units are measured. For example, the ETS currently does not account for different carbon sequestration rates in different species.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.