The 50 private huts hidden in the Orongorongo Valley

Fifty private huts, hidden in native bush in the Orongorongo Valley near Wellington, have played an important role for generations of families.

Words: Rebecca Jamieson Photos: Allan Sheppard and Rebecca Jamieson

Familiar sounds and smells surrounded me – a damp, earthy aroma common to the bush, the babble of a nearby stream and a riroriro’s welcoming karanga. They drew me in as I descended cautiously over tree roots and rocks to the valley below. I stopped midway on the Turere Bridge and the valley opened up before me. The braided river with its bush-clad sides; rata, red with flower, towering above the canopy to meet rugged, bare-faced ridges.

I carried a precious load that day – my three-month-old son John. He slept peacefully, lulled by the warmth of my body and gentle stride, unaware of the auspiciousness of the occasion.

It had been over a year since I’d been to my turangawaewae – Tahora Hut in the Orongorongo Valley. I was taking John home. When I caught my first glimpse of Tahora, among the ferns and trees, I hurried the last few metres to open the door as if greeting a long-lost friend. The reunion didn’t disappoint. Mismatched curtains from the 1970s still adorned the windows. The coal range at one end; Grandad’s old rocker at the other. I drank in the familiar musty smell and let the memories come.

Tahora was built in 1971 by my father Maurice Mitchinson and his friends. They were a rough-and-tumble lot in their late teens with shaggy hair, bell-bottom jeans and long, green Swanndris covering their lanky frames. But they had energy and attitude and were full of enthusiasm for the hard work of a good project ahead.

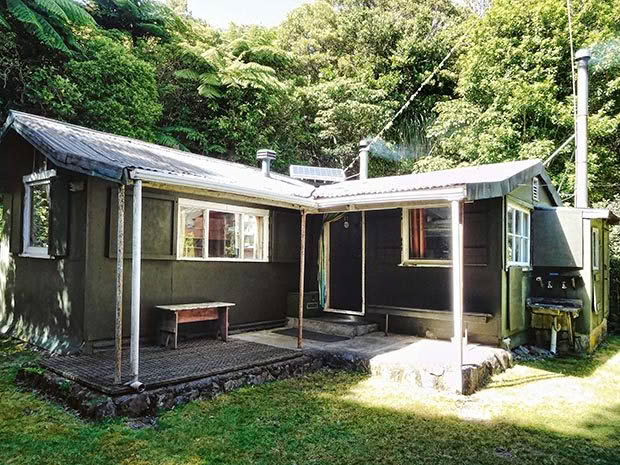

Our family hut, Tahora.

Dad was an apprentice carpenter, but during his study time he pulled nails out of Ford car-packing cases from which he could build a hut. The hut was pre-built in my grandparents’ backyard, then driven into the valley tied to a friend’s homemade buggy. Dad and his mates had cleared the hut site with axes and slashes before carrying bundles of dismantled pieces up the hill 300 metres to the building site.

Rules were relaxed back then; an application to the Wellington Water Board for a licence to build a hut was all that was required. By 1970 there were already 60 huts in the valley, some dating back to the 1920s and 1930s.

Outside Nikau Hut with my husband Jason and John in 2015. Nikau Hut was built from manuka poles and flattened kerosene tins, which were carried in from Eastbourne.

Early huts were constructed from whatever materials were at hand. Manuka poles for framing; flattened kerosene tins for cladding. Bags of concrete and rolls of malthoid were carried in from Eastbourne – a four-hour tramp.

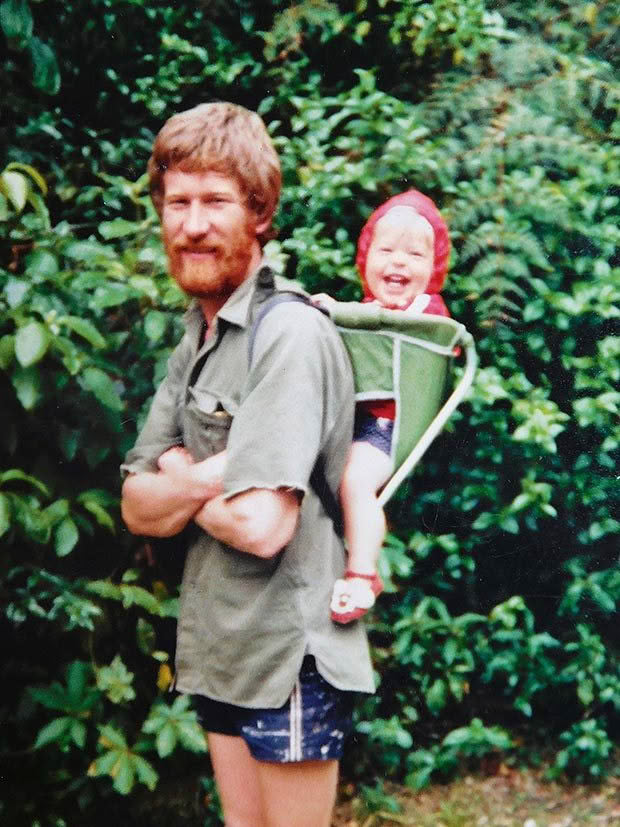

Tahora’s look and form has changed over the years – adapting to our growing family. It once was a bachelor pad where flagons were emptied and tall tales told. Today it is a comfortable family retreat where treasured childhood memories are still being created. I was younger than John for my first trip to Tahora. In 1983 at six weeks old, my mother carried me while my father filled his old aluminium-framed pack with food and clothes – he still carries that pack today. I slept cocooned in the lower bunk and was bathed in a bucket by the coal range. I’ve been in love with the place ever since.

Dad and me outside Tahora, 1985.

My younger sister and I had an idyllic childhood in the bush. We raced along the tracks between neighbouring huts and down to the river; constructed our own “huts” from fallen branches and ferns; swam in the deepest river holes we could find; toasted marshmallows on the open fire; ambled up river to visit family and friends and listened to children’s stories on National Radio. We read books or played cards by the light of lanterns then rested our tired bodies in our bunks, often lulled to sleep by the rhythmic drumming of rain on the tin roof or the call of a morepork.

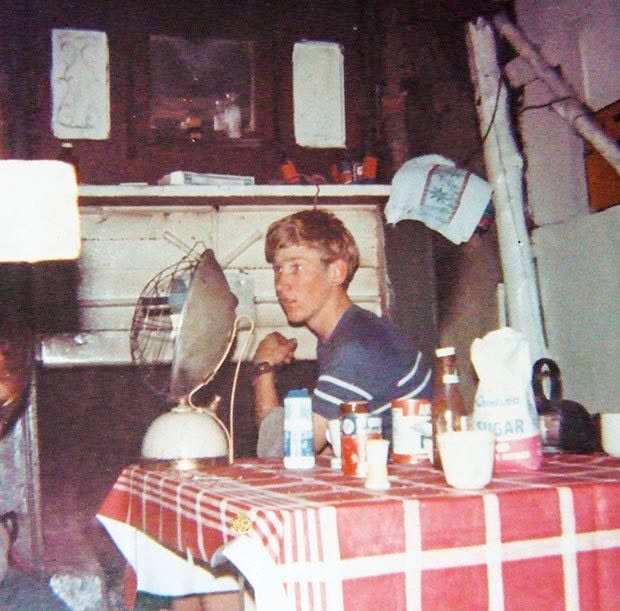

Dad at Kiwi Hut in the late 1960s.

We weren’t the only children to experience this kind of childhood; there were many kids in the valley when I was growing up. We played together and swam in the river while our parents caught up over a few beers at riverbed golf tournaments and hangis. Many of those friends now bring their children.

The valley also has a long history of introducing people to the great outdoors. Many private huts have been widely shared with other families, friends, school groups and international visitors. These first introductions can seed a lifelong interest in the outdoors for those who wouldn’t normally have the confidence and ability to experience the New Zealand bush.

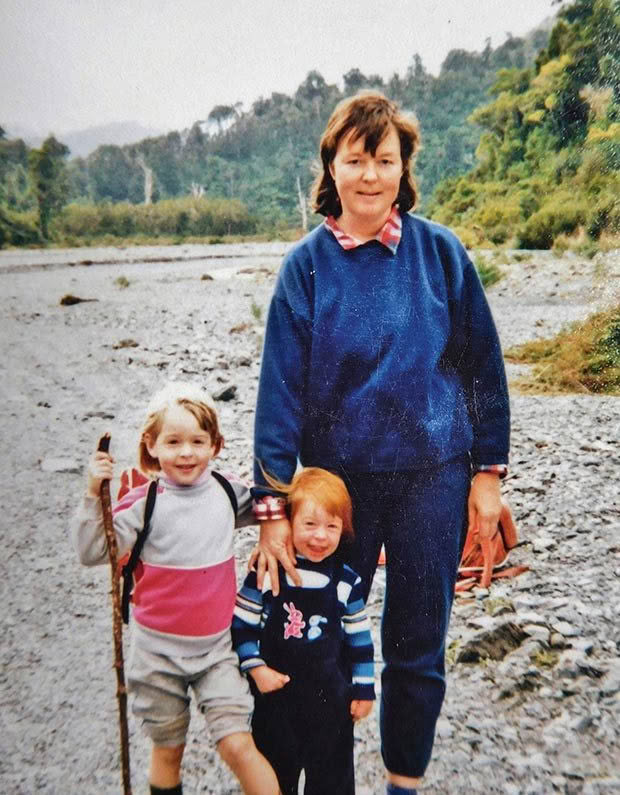

Mum, me and my sister Aimee 1988.

Tahora’s logbooks show nearly 200 people have enjoyed the hut over its 45 years. Six-year-old Corban stayed recently with his grandfather Wayne Butler, one of the original Tahora building crew. Corban recounted his experience for the log book.

“I am six years old. Maurice made me a bow and arrow and I have learned how to make it go 8.7 metres. I love it. I have learnt how you cook tea on the coal range and porridge on the primus. Last night I heard a new bird sound in the bush – a morepork. I am definitely coming back again.”

In 1995 the Orongorongo Club started the kids’ Easter Moa Hunt competition. The valley’s children spend the weekend trapping pests and hunting for items on their scavenger list such as a coprosma berry or kawakawa leaf. Last year 130 possums were entered – a good dent in the local pest population.

The competition ends with the famous billy-boiling challenge, which teaches children how to light fires safely. More than 30 children took part in the Moa Hunt last year; many are third- and fourth-generation Orongoites.

The bunkroom was added onto the hut in 1972 to accommodate my dad’s parents and sisters. Dad added on the sides to the top bunks after I fell out as a kid.

My experiences in the valley have had a huge impact on the person I am, and have strongly influenced my career path. Growing up, it was my sanctuary and as a teenager it grounded me when I really needed it. I grew a passion for the outdoors and, when I was young, I decided to work in conservation. After I completed a Bachelor of Parks and Recreation Management, I worked as a park ranger for councils and for DOC in visitor, community and heritage roles.

Others who have grown up in the valley have studied resource management, geology, botany and pest management. Some volunteer for Search and Rescue and maintain trap lines for the Rimutaka Forest Park Trust kiwi project.

Despite the valley’s private huts providing hundreds of children with the opportunity to connect with nature, their future is tenuous. Current licences end with the death of the licensees without the ability to transfer them to family. Many licensees are now in their 60s, 70s and 80s – and time is running out. The Orongorongo Club is advocating for transferability for future generations and is negotiating with DOC to try and achieve this.

If the licences remain unchanged, only the five public huts will eventually remain, effectively reducing the number of families able to enjoy the valley. There will still be children there, but perhaps not those who are able to form a deep and long-lasting love of nature that comes with regular and easy access to the outdoors. My son’s generation may be the last children of the Orongorongo huts community.

Dad, John, me and my mum, Margaret, outside Tahora at Easter last year.

It’s been nearly four years since that auspicious first trip into the valley with John. Since then I have experienced great joy in watching him grow up in the valley like I did. John loves going bush to “Grandad’s hut”. He spends most of such weekends leading my father on “jungle” adventures around the network of tracks connecting neighbouring huts or inspecting the inhabitants of the nearby Brown’s Stream. My husband’s family recently got together for their own hut’s birthday. Nikau Hut was 75 years old last year, built by John’s namesake, his great-grandfather John Farrell.

I met my husband outside of the valley only to realize we both had family huts – maybe not just a coincidence but fate. We have further family connections in the valley and there is something special about our families’ histories being intertwined with the Orongorongos.

John with his cousin April Carswell showing off the possums caught at the kids’ Easter Moa Hunt last year.

The original builders perhaps didn’t foresee the impact the huts would have on future generations and how important it would be to provide an opportunity for deep connections with a natural place and a sense of real community in an increasingly virtual world. If they disappear from the valley, a piece of us will disappear with them. They are our turangawaewae – our place to stand, our home.

WHAT WE’LL BE EATING AND DRINKING

“I love a cold cider in the summer and it tastes even better from our stream-fed cooler outside the hut. I recently discovered a delicious local cider made in Greytown – Forecast Cider. It goes well with venison steaks and salad – our favourite bush summer meal – if my husband gets lucky hunting. Dessert is often the instant packet variety whizzed up with a hand beater and set in our small gas freezer box.”

The old Shacklock range is great for cooking pikelets, scones and even the odd roast mutton.

WHAT WE’LL BE READING

“I plan to catch up with Deborah Challinor’s latest novel The Cloud Leopard’s Daughter. There’s also a shelf full of old Reader’s Digests in the hut if we run out of books to read – the “Laughter is the Best Medicine” section has provided lots of entertainment over the years. At bedtime, I squeeze in with John on the top bunk and read his favourite Kapai, the Kiwi and Little Kiwi books.”

THE GAMES WE’LL BE PLAYING

“When we’re not lazing about drinking cider and reading in the sun, we like to walk to neighbouring huts for a visit and swim down at the river. Back at the hut, John likes to play endless games of Snakes and Ladders and Snap – we’re looking forward to when he’s old enough for a game of Scrabble. The old transistor radio also provides entertainment with children’s stories on National Radio. If we’re lucky we can sometimes tune into The Sound for our favourite, old rock classics.”

SHARE A STORY

If you have experienced an overnight stay at one of the valley’s private huts, please share your story with the Orongorongo Club at orongorongoclub.org.nz

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Life & Leisure Magazine.