5 common egg imperfections and what they say about your chickens

Even if the outside of an egg looks perfect, there can be little horrors waiting for you inside.

Words: Sue Clarke

All those years of cracking open perfect supermarket eggs might have made you think all eggs are like that.

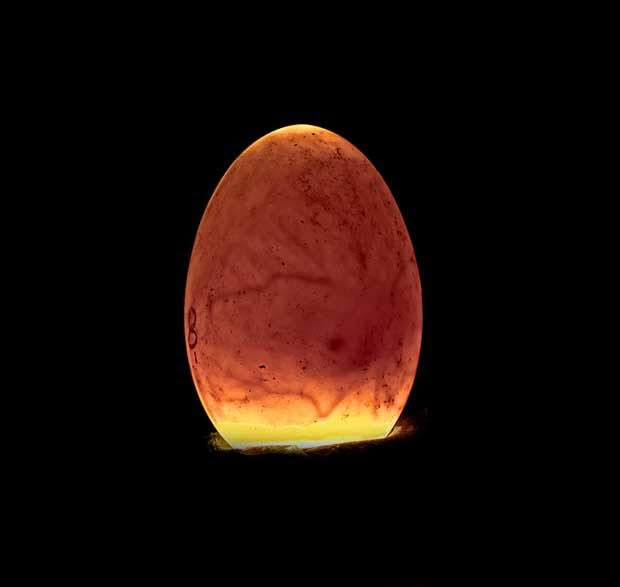

But it’s careful management which gets you perfection every time. Eggs sold in large commercial quantities go through a thorough checking process: any eggs with obvious damage or imperfect shells are removed. They then pass over a bright ‘candling’ light which highlights finer cracks and any internal defects. The eggs are then packaged by weight.

For those gathering eggs from their own hens, the best advice I can give you is to always crack an egg into a bowl, just in case the contents are not what you’re expecting. That way, you don’t end up with something nasty in your half-prepared cake mix or omelette.

While many of the unusual findings within an egg are ok to eat, they don’t tend to look appetising. Every now and then, it will be something really disgusting. The worst is an egg gone bad, one that has been invaded by bacteria, creating an explosive green, grey gassy… mixture. There is often nothing on the outside to give you a warning. This is why we advise doing a ‘float’ test: an egg that is fresh will sink to the bottom and lay on its side. Older eggs float as the porous shell will have allowed air, and possibly bacteria, to infiltrate it. It’s better to discard an egg that floats.

1. WHITES THAT AREN’T WHITE

A freshly-laid, still warm egg white (albumen) may have a slightly cloudy appearance, caused by the CO2 within the egg. It soon dissipates through the pores of the shell once the egg cools down.

Any other oddly-coloured ‘white’ indicates a problem:

• yellow means the egg is old;

• green can mean an excess of riboflavin in the diet, or that a bird has eaten a weed called shepherd’s purse;

• dark green indicates a bird has eaten oak or acorns (especially in ducks);

• fluorescent green can indicate the presence of bacterial contamination;

• pink and watery is a sign a bird has been eating mallow (a common weed).

Shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursapastoris).

Watery whites can be an indicator of a viral disease condition like infectious bronchitis. It can also cause pale shells, deformed shells, and shell-less eggs, but not necessarily physical symptoms in a hen.

The white of an egg will also get thinner, the longer the egg is stored. Higher temperatures will speed up this effect.

Other causes of watery whites are the age of the hen, storage time, genetics, and the time taken for the eggs to cool down in the nest. This is why collecting the eggs more frequently in hot weather is important.

Mallow (Malva neglecta).

Fungal toxins from stale, wet or mouldy feed can be a factor as well.

The higher the thick white (which surrounds the yolk) sits, the fresher it is. Commercial hybrids have the genetics for firm, high albumen height (measured in Haugh units), but storage of eggs for long periods, at temperatures above 15°C and in low humidity, will increase the incidence of watery whites.

2. BLOODY EGGS

Blood spots or large quantities of blood surrounding the yolk indicate a rupture in the hen’s ovary as the yolk was released. It is not a chick embryo. A partially-incubated egg would show as a network of veins over the yolk radiating from a central point. Neither would be nice to find or eat, although your dog may disagree.

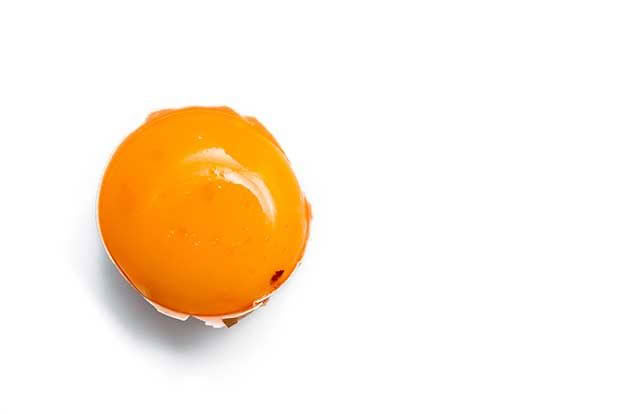

Blood spot: This is a little bit of blood released as the yolk is released by the ovary.

A small inclusion which is pinkish and usually found in the albumen, not in the yolk, is called a meat spot and could be a piece of oviduct tissue which has come free and been included inside the contents before the membrane is formed.

An embryo: The early development of a chick appears as little veins of blood, going to a central point.

3. ANOTHER EGG

An egg within an egg can occur when a fully-shelled egg gets held up in the oviduct and either a complete egg, including yolk, gets combined within one very large shell, or the original egg gets an extra coating of albumen and another shell.

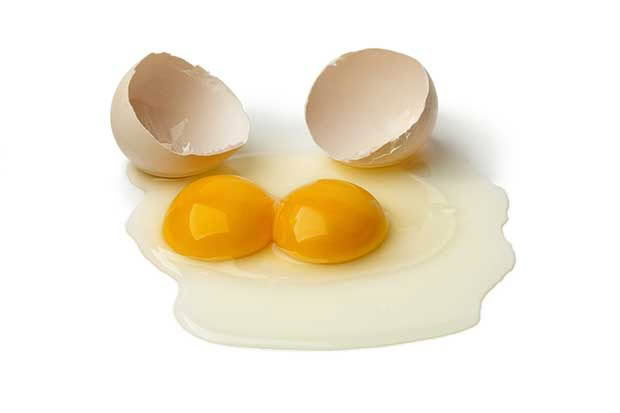

Double yolker: The accidental release of two yolks by the ovary of a hen – one will be slightly larger than the other.

This is an error in timing for a hen, the same as for a double yolker which is when two yolks are released from the ovary at the same time and are combined within one larger shell. This can be an issue with some breeds which are multi-ovulators, or for young hens just starting to lay before the regular ovulation of one yolk per day is established.

4. YOLK COLOUR

This is not a sign of the quality of the egg, but an indication of what the bird has eaten.

Foods which contain carotene and chlorophyll such as orange vegetables, flowers, maize, grass and leafy vegetables, deepen the colour of the yolk, and the colour of the skin and legs of theh en (if they are a yellow-skinned breed).

Commercial feeds may contain synthetically-produced food grade colourings or naturally-occurring ones like maize, marigold petals, or turmeric, to give yolks more colour when hens don’t have access to grass or naturally yellow foods.

The depth of the preferred yolk colour varies around the world. The Germans prefer their yolks to be dark orange (61% of the population), but the same colour isn’t as popular in the UK (31% of the population), while 17% of UK citizens prefer their yolks to be pale.

5. SHELL COLOUR

A commercial feed often contains enough Vitamin D3 for birds that would normally be kept inside a commercial shed and not see sunlight.

But this can cause a condition in free-range hens, especially in high sunlight areas like Marlborough. The extra vitamin D3 causes brown eggs to get paler and paler. Excess calcium can also cause brown eggs to become paler.

Shell colour is a breed characteristic and is inherited:

• light breeds like Leghorns and Minorcas tend to lay white eggs;

• heavy breeds like Rhode Island Reds lay brown eggs;

• many breeds lay beige or light brown eggs.

Commercial hybrids like Shaver Browns and Hyline Browns both lay very brown eggs. They are the result of a two-way parent cross which combines the genes from a heavy breed and a light breed in one bird. This emphasises the genes for light body size and high egg numbers of a small breed (eg, Mediterranean breeds), and the egg colour and shell strength of the heavy breeds (eg, Rhode Island Reds). The ‘brownness’ of an egg is a colour laid over a basic white egg. If you pick up a hot, wet, freshly-laid brown egg, the colour may actually smudge where you touch it.

The saying that birds with white ear lobes lay white eggs and birds with red ear lobes lay brown eggs is almost true, but there are a few exceptions:

• Silkies have turquoise blue or dark red ear lobes and lay creamy white eggs;

• Sebright bantams have red ear lobes and lay white eggs;

• Araucanas have red ear lobes and lay blue or olive green eggs.

The colour of an Araucana egg is a genetic anomaly, connected with bilirubin levels in the liver which contribute to the distinctive blue-green hue. An olive egg is a basic blue with the gene for brown ‘paint’ overlaying the blue, just as the egg is ready to be laid. It is a strong genetic trait, so a crossbred hen that lays eggs with a green or blue tinge has Araucana in it somewhere.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.