5 amazing food forest gardens

A food forest can take up half a lifestyle block or be as small as an urban backyard, but the combination of fruit trees, berries, vines and vegetables – and in some cases animals – can create a resilient, self-sufficient garden that will feed you and your family all year-round.

When you arrive at the Koanga Institute, hidden in a remote valley an hour’s drive south-west of Gisborne, it’s a wild-looking place.

The beds where the Institute’s precious heritage seeds are grown is easily identifiable as a ‘normal’ garden with plants in neat rows, the corn standing in groups, the seedlings sitting in uniform trays under nets to stop the birds getting in first.

But all around it is a wilderness that seems bewildering in contrast, seeming to make no sense, until your guide arrives.

Shaked From (pronounced Shar-ked) grew up on a kibbutz in Israel. He looks a little wild, a bit like the garden he cares for, but you can feel your enthusiasm begin to bubble as he talks you through what is the beginning of a substantial forest garden around the big old villa that is the headquarters for Koanga.

If you’ve ever wanted to plant a food forest but found the whole concept daunting, or think your garden is too small, we look at how Koanga are doing it, plus see what can be achieved over 5, 10 and 20 year periods in some other forest gardens from around the world.

WHAT IS A FOREST GARDEN OR FOOD FOREST?

The concept of the forest garden or food forest comes from nature.

People living in tropical rainforests would have identified edible crops such as fruit trees, vines, bushes, ground covers and roots, then cultivated more.

Forest gardens in cooler, temperate climates have to be more carefully designed as the sun doesn’t penetrate through the layers to provide the same amount of light and heat as tropical forest gardens receive. This means you need to either carefully choose shade-tolerant perennials for your garden, or create open, light-filled glades to allow the lower levels of canopy to grow.

There’s no one type of food forest, as the trees and plants will vary depending on where you live, your climate and what does best in your region. However, the basic design is made up of seven layers: canopy trees, shrubs, perennial vegetables and herbs, root crops, ground covers and vines/climbers.

While most of the plants provide food, some are included purely for their nitrogen-fixing abilities, shade and shelter, flowers for pollination, and habitat. Most forest gardens include large amounts of medicinal herbs too.

There are several key features of a forest garden system:

• large numbers of different species of trees, shrubs, ground covers, climbers and root crops to create as much diversity as possible

• the use of nitrogen-fixing trees and plants

• the use of deep-rooting plants (known as dynamic accumulators), eg comfrey, sorrel

• the use of hardy, disease-resistant varieties

1 Canopy trees, highest layer, eg chestnuts, persimmon, honey locust, Siberian pea trees, hawthorns, apples, pears, plums, medlars, mulberries.

2 Low tree layer, small trees and large shrubs, eg dwarf fruit trees, bamboos, limes.

3 Shrub layer, shade-tolerant, eg currants, berries, flax.

4 Herbaceous perennials, eg comfrey, beets, herbs, mints, sage, tansy.

5 Rhizophere (roots), eg root vegetables, liquorice.

6 Soil surface, ground covers that creep and form carpets, eg ginger, strawberries.

7 Vertical layer, climbers and vines, eg kiwifruit, grapes.

KOANGA INSTITUTE

Where: Wairoa, 80km south-west of Gisborne

Area: 1ha (2.5 acres)

Climate: warm, temperate, good rainfall

Soil: pumice, topsoil

First planted: 2011

There’s no forest as such to see at Koanga, except for the huge swathes of pine trees on the distant hills, but the Koanga Institute’s garden team can see exactly where it will be. So can the other integral members of the workforce, a flock of Chinese ‘weeder’ geese that honk their way around the trees.

Chinese ‘weeder’ geese keep down the grass around fruit and nitrogen-fixing trees.

“Our forest garden is based in part around animals, which is quite interesting,” says head forest gardener Shaked From.

“You go into all of these beautiful amazing books (on forest gardens) and none of them speak much about animals, but that’s impossible for us at Koanga – when we design, we look at how this is going to work for us.

“Mainly it’s nutrition and we speak about nutrient dense foods – a lot of what we understand is based on several sources. One is Weston A Price and his book Nutrition and Physical Degeneration and what we take from it is that a lot of our nutritional needs are actually coming from animals and it would be really hard – if not impossible – to get it from plants.”

Shaked points out the different trees that will make up the forest garden’s canopy.

The geese are part of the garden at the moment, working to keep the grass and weeds at bay so the trees can get growing.

“In most forest gardens, what they do is kill all the ground cover, then put new ground cover in, then they start to build on top of that. The problem for us with that is you can’t have animals in there for so long because the environment is so fragile but we do want the animals here so the geese keep the grass down. They’re also food for us and they lay eggs.”

The fruit trees in the forest garden are all part of the Institute’s heritage collection and are used for scionwood. They also had to be planted first, so the other canopy trees that followed were all carefully chosen to play multiple roles in the ecosystem of the forest garden.

Siberian pea shrub is an important plant, providing food for poultry and fixing nitrogen.

“We pick plants that are going to support these trees, but are also going to be food for us and for the animals. The most common one is tagasaste (tree Lucerne, Cytisus proliferus, formerly Chamaecytisus palmensis) which is beautiful fodder for rabbits and for raising animals, it has edible seeds for chooks, poultry, and it’s a nitrogen fixer.”

Other important trees include phosphorus-accumulating sheoaks (Casuarina cunninghamiana) and nitrogen-fixing Siberian pea tree (Caragana arborescens) which is also edible for humans and for animals.

“We look at the size of the canopy of the trees,” says Shaked. “We want our heavy croppers, the apples and peaches and that kind of stuff, to be well and get a lot of sun. Our support plants need to be shorter and not need so much sun.“Each time we cut (tagasaste) we feed the branches to the apples which gets a balanced mix of minerals to the apples, and at the same time it (tagasaste) self-prunes its roots (to match the canopy of the tree), and the roots fix nitrogen in the soil for the roots of the apples too.”

Other trees that suit the at-times water-logged soils at the Institute’s site include a host of trees that do duty as shelter and nitrogen-fixing canopy trees: Italian and red alders, tree medick (Medicago arborea), various acacia species and maackia (Maackia amurensis). The next step for Shaked is to start planting out the lower canopy trees.

A sheaoak (foreground) is strategically placed to assist with the fertility of the soil around the closest fruit tree (background) when fully grown.

“Slowly the environment here will change because the fruit trees will shade the grass, there will be a whole heap of tagasaste, then some lower bushes so it’s another layer and the grass will be shaded out more. Slowly there will be less and less food for the geese and then we’ll start bringing in chickens because there will be a whole heap of food for them.”

The garden is already providing food for itself and its gardeners.

During summer the tagasaste was pruned each week to use as mulch for the fruit trees, they picked the first crop of peaches, then figs, and cardoon (Cynara cardunculus) stems were cut for mulch. The ultimate aim of this forest is ambitious, but with careful design and by using plants that will thrive in the Institute’s micro climate, it is achievable says Koanga’s founder, Kay Baxter.

“Our goal is to create a local, regenerative, resilient system that provides us with highly nutritious food and other basic human needs, while being efficient and easily manageable.”

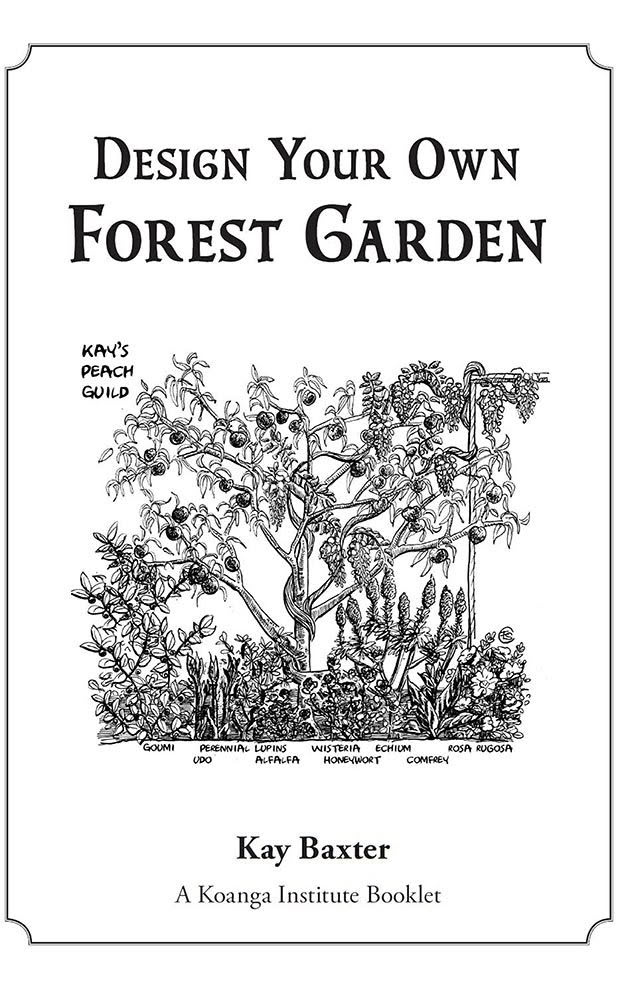

Design Your Own Forest Garden By Kay Baxter is available from Koanga Institute, 32 page booklet, $12

This new booklet from Koanga is written for the home gardener who wants to create their own forest garden and provide as much of their own fruit, nuts and nutrition as possible. It includes a guide to the basic design elements and lists of possible plants, a calendar so you can work out what plants will provide you with food all year-round, and shows you how to calculate a nutrient budget for your garden.

SCHUMACHER FOREST GARDEN PROJECT

Who: Martin Crawford

Where: South Devon, England

Area: 0.8ha (2 acres)

Climate: Temperate, cool

First planted: 1991

This forest garden was inspired by the legendary work of English forest gardener Robert Hart and is described by Dave Jacke (author of Edible Forest Gardens) as one of the best examples he’s ever seen.

It’s the creation of agroforestry expert Martin Crawford, just one of his experiments on how perennial trees, shrubs and other plants can create a sustainable food production system in a cooler climate.

These days Martin describes how he can walk into what looks like natural woodland, with no bare soil to see. He’s carefully chosen a wide variety of perennial plants to cover the lower layers and concentrated on more unusual edibles and, as with many permaculture gardens, the trees and plants provide fruit, nuts, leaves, medicinal plants, timber and firewood.

Young hosta shoots are a great edible addition and are happy to grow in the shade.

At ground level in early spring, Martin says he can feast on a huge range of plants, from the delicious-tasting, potato-like roots of Solomon’s seal (Polygonatum biflorum), to spears of Good King Henry spinach (Blitum bonus-henricus) and bamboo shoots.

Another popular edible in spring is the slightly bitter tasting, still rolled-up young leaves of many varieties of hosta which can be fried up in a little oil. It’s also possible eat the young shoots and flowers of many hosta varieties.

Other unusual edibles include a Szechuan pepper tree (Zanthoxylum schinifolium). Its small fruit can be used in place of peppercorns but apparently have a more spicy aftertaste.

Japanese pepper tree fruit.

There’s also a type of dwarf-like member of the chestnut family that grows to 5m called the chinkapin (Castanea pumila) which produces a small edible nut. In the bottom layer is a huge range of herbs including mints, tansy, oregano and lemon balm, shade-tolerant Japanese blackberry (Rubus trifidus), and raspberry varieties which Martin leaves to grow along the ground so they are not so obvious to birds.

RISC ROOFTOP FOREST GARDEN

What: The roof of the Reading International Solidarity Centre

Where: Reading, 70km west of London

Area: 210m²

First planted: 2002

No. of plants: 185

Climate: temperate, cool

Soil: recovered soil & compost to a maximum depth of 30cm

This amazing garden was once an ugly, leaking roof but is now a productive, food-producing garden, plus it acts as heat and sound insulation for the conference centre below.

Once engineers okayed the roof for the extra weight, it was repaired and then lined so run-off could be stored in tanks. It catches rainwater which is stored in butts for use as irrigation over summer, with power for the pump supplied by energy from solar panels and a wind turbine.

All the hard landscaping was built using local waste materials: wind-blown oak, coppiced hazel, recycled plastic and old paving.

All the plants are edible or have medicinal properties, or can be used for fuel, fibre, construction, dye or scent.

The garden is mulched with compost (made using scraps from the on-site cafe), newspaper and bark chips, and maintenance like pruning and weeding is done by volunteers. Head gardener Dave Richards says he was initially worried the trees would not thrive in the shallow soil but after three years the larger ones, including crab apples, dessert apples, plums, cherries and pears, all had to be pruned back to keep their height to a manageable level.

The roof acts like a heat sink, so the garden supports a range of heat-loving plants that normally don’t grow in the area. In the spirit of growing the more unusual, this forest garden has some intriguing layers to it.

You can see a list of all the plants in it by clicking here, but some of the interesting ones include:

• Strawberry tree (pictured above), Arbutus andrachne – the fruit tastes similar to strawberries.

• Black bamboo (above), Phyllostachys nigra, for food and shelter

• Toothache tree (below), Zanthoxylum planispinum, peppery flavour.

• Blue sausage tree (below), (Decaisnea fargesii), fruit have a jelly-like centre that tastes like watermelon.

• Japanese mountain banana, Musa basjoo, used for its fibre.

• June berry, Amelanchier canadensis, sweet-tasting blue-black fruit.

• Black chokeberries, Aronia arbutifolia, used for preserving.

The berries include black mulberry, red, black and white currants, blueberries, raspberries, strawberries, and wild strawberries that are a rampant ground cover. Vines on the outer walls include kiwifruit and grapes, chocolate vine (Akebia quinata) and golden hops. There are a lot of flowering plants that could be eaten but are left to go to flower and then seed including Welsh onions, garlic, chives, Echinacea, liquorice and fennel.

CHERONNAC FOREST GARDEN

Who: Steve & Yvonne Page

Where: Chéronnac, about 400km south of Paris, France

Area: 3600m²

First planted: 1992

No. of plants: 400 species, including persimmon, dates, figs, peaches, kiwifruit, nuts, and berries

Climate: cool, temperate

Soil: sandy loam

Steve’s 10 tips for setting up a successful forest garden

• Plant a windbreak before you start planting anything else.

• A forest garden is easiest to maintain at shrub level.

• Don’t have too many tall trees, and plant them on the north side of the garden (south in NZ) so they don’t shade out the smaller trees and shrubs.

• Keep the amounts of grass to a minimum, if any.

• Design in paths so all parts of the garden are easily accessible.

• Dig swales along contour lines, to retain water within the garden.

• Plant a good mix of edible plants, nitrogen fixers, dynamic accumulators and those that attract wildlife, especially insects.

• Plant things that ripen at different times through the year.

• Use fallen trees as climbing frames for other plants.

• Remove as little nutrients as possible from the garden. Leave dead trees and don’t harvest all fruit so some nutrients are left.

DEEP GREEN FOREST GARDEN

Who: Angelo Eliades

Where: Melbourne, Australia

Area: 85m²

First planted: October 2008

Climate: cool, temperate

Soil: sandy loam

Fruit trees: 30+ including lemon, apple, lime, pear, cherry, fig, passionfruit, plum, apricot, babaco, grape, peach, nectarine, orange, banana, feijoa, grapefruit, pomegranate

Berries: 16 different types including raspberry, blueberry, blackcurrant, redcurrant, goji berry, cherry guava, mulberry, blackberry

Medicinal herbs: 70+ types

Blog: Deep Green Permaculture

Angelo Eliades was already an accomplished gardener but in 2008 he stumbled across the concept of permaculture. That winter, he set about turning his tiny backyard into a permaculture oasis, producing huge amounts of food.

“The vertical stacking of trees and plants creates an intensive planting system which, when recreated with edible plants, produces very high yields.

This close arrangement of plants also creates a very distinct microclimate, which allows plants to grow in a protected space where they are not assaulted by the elements.

“An intensive, mixed planting of various species creates a biodiverse environment which allows synergy between plants, where plants help each other grow, protect each other from pests and diseases, and increase productivity. This is the concept of companion planting.”

On his blog, Angelo outlines the garden’s annual production of fruit, berries and vegetables:

2009 133kg

2010 204kg

2011 196kg

2012 234kg

Average monthly amount: 19.5kg

Yield per hectare: 36.6 tonnes

Angelo’s garden includes a home-made water storage system (1500 litre capacity) that collects water off his garage roof as Melbourne residents mostly live under water restrictions over summer due to drought.

Pests haven’t been a problem, and when it comes to weeds, Angelo explains how the forest garden system copes:

“I have replicated the stacking system that occurs in nature: tree canopies with shrubs below them, herbaceous plants below those, and ground covers protecting exposed soil. Root crops fill the subterranean regions, and climbers vine and snake in the vertical plane. The natural leaf fall creates a sheet mulching/sheet composting system so there is no bare soil. What I’ve found is that with no space or light available for fallen seeds, no seeds grow. Not even ‘weeds’.”

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.