3 inspiring New Zealand food forests

We take a guided tour through three very different food forests at different stages in their lifecycle.

Words: Carl Pickens

When it comes to comparing food forests at different scales and stages of development in New Zealand, we’re not overly spoilt for choice. I’m not talking here about the many small examples scattered throughout New Zealand on rural properties owned by those with a penchant for sustainability, but accessible examples on public land.

New Zealand councils have been slow to adopt practices already taken up overseas, such as planting fruit trees in public parks, although it’s encouraging to see Christchurch City Council developing policy in this area.

The US city of Seattle has allocated 3ha of public land to a food forest, just a few kilometres from the city centre. This food forest will include an edible arboretum with fruits gathered from regions around the world, a berry patch for canning, gleaning and picking, a nut grove with trees providing shade and sustenance, a community garden for families to grow their own food, a gathering plaza for celebration and education, a kid’s area for education and play, and a living gateway to connect and serve as portals as you meander along.

The following are three modest examples of food forests I have either been directly involved in creating, or know about via colleagues and friends, all in the upper North Island. Two of these are open to the general public, with another private example.

WAIHI ACADEMY OF STUDIES

Size: 0.6ha (1.5 acres), but planned to eventually cover 1.6ha (4 acres)

Established: 2012

Crops: berry varieties (including blueberries, goji), heritage fruit trees, oolong tea

Climate: warm summers that are not particularly humid, cool winters with the occasional frost to knock back insect pests

Soil: pretty good at this particular site, moderately fertile, reasonably free draining clay loam, with a good amount of sand and silt to balance out the clay component

Problem: boron deficient soil

Year 2: the Waihi food forest is planted out into a crop of tick beans, including heritage fruit trees and nitrogen-fixing tagasaste, in 2013.

The Waihi Academy of Studies is a school and retreat facility near Waihi, at the southern end of the Coromandel Peninsula. The trust that runs the academy has built an impressive modern facility where it hosts students from overseas and locally, giving them an experience of the New Zealand rural environment and Asian culture. It also runs retreats, covering topics such as tai chi, herbal medicine and calligraphy.

Currently, the land includes a BioGro-certified kiwifruit orchard, contract maize growing, and forestry plantings. The philosophy at the Academy includes looking after the natural environment, so I didn’t have to convince anyone that approaching their project using organic principles was a good thing.

As part of the learning culture encouraged at the Academy (which includes interaction with the natural environment), I have been engaged to help develop a food forest area, taking over land from contract maize production. If you know anything about growing maize/corn you’ll know that it is very hard on the land. This very hungry plant strips the soil of nitrogen and whatever else it can get its hands on. The contract growers had been managing this area conventionally and using chemical fertilisers to sustain growth. While this isn’t ideal, at least there was very little kikuyu to worry about.

Although it wasn’t sowed, clover is one of the plants colonising the soil around the trees.

Time was against us in the beginning (winter was approaching), so after the corn harvest we sowed a green manure crop of tick beans, a nitrogen fixer that performs well at lower temperatures. We crossed our fingers at this point, hoped for the best, and luckily the seed germinated and the plants put on some growth before winter kicked in.

In September 2013 we planted fruit and nitrogen-fixing trees directly into this green manure crop. It involved setting out where everything should go (I drafted a plan to follow), dusting mycorrhizae fungi on the bare-rooted fruit trees, and mixing compost in some rather large planting holes. We purchased compost from Environmental Fertilizers in the nearby town of Paeroa, a good local source of high quality compost.

We then put plant guards around the many small trees to protect from browsing (rabbits are common) and staked the larger trees as the site is windy. A working bee two months later placed cardboard and mulch around the trees, the mulch helping retain soil moisture through the critical first few summers. There were a couple of interesting observations. While the tick bean ground cover grew reasonably well, what really surprised me was the amount of clover that came out of nowhere and colonised the ground. The seed must have been sitting in the ground waiting for the right conditions to germinate.

The long grass and weeds provides excellent shelter.

The nitrogen-fixing tagasaste surprised me too. It put on top growth so quickly that the persistent prevailing winds rocked the under-developed root systems and started killing off trees. We were caught out by an insufficient frequency of site visits in the early stages and didn’t catch this early enough, so we scrambled and cut back the top growth to allow the root system to better develop, in order to cope with the winds. We did some more staking too.

It’s important to note the Academy is run as a non-profit trust, so there isn’t a lot of money to throw around and it relies mainly on volunteers to continue development and maintenance of the food forest. Luckily we have a core team of 10, some of whom are experienced gardeners. Three to four times a year the groundcover around the trees (which now consists of whatever emerged with the clover such as wild carrot, fennel, dock, plantain, a bit of kikuyu, some thistle) gets mowed. We are experimenting with a natural farming technique of letting the weeds grow and mulching heavily around the trees only (using layered branches on the ground for airflow with thick brush on top), and have left enough room around each tree or cluster of trees for the ride-on mower to get around if need be.

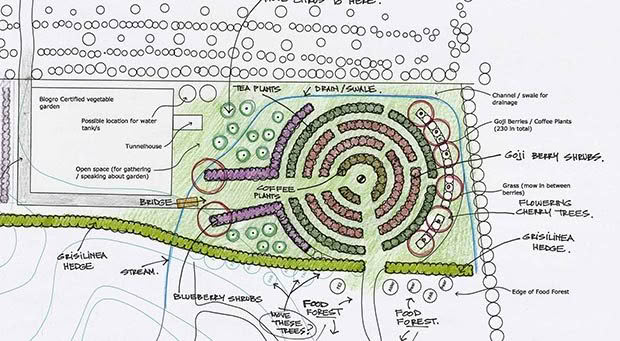

Carl’s planting plan showing the berry plantings.

The trees were watered three times by hand through the first summer – picture a ute with a 1000 litre container on the back and a hose coming out the back – just to keep them alive. Despite this being a low budget project, we did spend good money initially on mostly heritage variety fruit trees such as Arapahoe Red Leaf peaches and Monty’s Surprise apples.

The berry and oolong tea garden has been developed on land left lying fallow for many years. This land had a lot of heavy machinery running over it when the Academy buildings were being built and subsequently the underlying soil was well compacted and poorly drained (it pooled with water in winter). We sought to improve it by having a contractor plough the existing grass and weed cover, rip the soil to improve drainage, contour to eliminate humps and hollows, then finally rotary hoe in a sprinkling of lime and compost.

Soil test results still showed deficiencies in boron, potassium, and phosphate after this treatment, so we applied organiBOR (a BioGro-approved form of boron) and rPr (rock phosphate), rotary hoed it in, then set about planting. The oolong tea was planted in October 2014. Plants have been laid out in a circular pattern (I’m fond of curved shapes in the landscape) which fitted well with the shape of the area. Once we’d added a few gaps here and there we had the makings of a maze and that will be fun for students in the years to come.

We also put plant guards around the oolong tea plants (as we did the trees in the food forest), and mulched heavily using the stick and brush method. One interesting observation was the extent to which the ripping and contouring worked. The soil went from a poorly drained, somewhat soggy area, to a fairly porous, somewhat fluffy soil ready for planting.

Inga edulis, the ice cream bean, named for the pod’s juicy pulp that tastes like vanilla ice cream.

The Waihi Academy of Studies is a school and retreat facility near Waihi, at the southern end of the Coromandel Peninsula. The trust that runs the academy has built an impressive modern facility where it hosts students from overseas and locally, giving them an experience of the New Zealand rural environment and Asian culture. It also runs retreats, covering topics such as tai chi, herbal medicine and calligraphy.

Currently, the land includes a BioGro-certified kiwifruit orchard, contract maize growing, and forestry plantings. The philosophy at the Academy includes looking after the natural environment, so I didn’t have to convince anyone that approaching their project using organic principles was a good thing.

As part of the learning culture encouraged at the Academy (which includes interaction with the natural environment), I have been engaged to help develop a food forest area, taking over land from contract maize production. If you know anything about growing maize/corn you’ll know that it is very hard on the land. This very hungry plant strips the soil of nitrogen and whatever else it can get its hands on. The contract growers had been managing this area conventionally and using chemical fertilisers to sustain growth. While this isn’t ideal, at least there was very little kikuyu to worry about.

Time was against us in the beginning (winter was approaching), so after the corn harvest we sowed a green manure crop of tick beans, a nitrogen fixer that performs well at lower temperatures. We crossed our fingers at this point, hoped for the best, and luckily the seed germinated and the plants put on some growth before winter kicked in.

In September 2013 we planted fruit and nitrogen-fixing trees directly into this green manure crop. It involved setting out where everything should go (I drafted a plan to follow), dusting mycorrhizae fungi on the bare-rooted fruit trees, and mixing compost in some rather large planting holes. We purchased compost from Environmental Fertilizers in the nearby town of Paeroa, a good local source of high quality compost.

We then put plant guards around the many small trees to protect from browsing (rabbits are common) and staked the larger trees as the site is windy. A working bee two months later placed cardboard and mulch around the trees, the mulch helping retain soil moisture through the critical first few summers. There were a couple of interesting observations. While the tick bean groundcover grew reasonably well, what really surprised me was the amount of clover that came out of nowhere and colonised the ground. The seed must have been sitting in the ground waiting for the right conditions to germinate.

The nitrogen-fixing tagasaste surprised me too. It put on top growth so quickly that the persistent prevailing winds rocked the under-developed root systems and started killing off trees. We were caught out by an insufficient frequency of site visits in the early stages and didn’t catch this early enough, so we scrambled and cut back the top growth to allow the root system to better develop, in order to cope with the winds. We did some more staking too.

It’s important to note the Academy is run as a non-profit trust, so there isn’t a lot of money to throw around and it relies mainly on volunteers to continue development and maintenance of the food forest. Luckily we have a core team of 10, some of whom are experienced gardeners. Three to four times a year the ground cover around the trees (which now consists of whatever emerged with the clover such as wild carrot, fennel, dock, plantain, a bit of kikuyu, some thistle) gets mowed.

White sapote, a tropical fruit from Mexico that tasted like a mix of vanilla cream and custard.

We are experimenting with a natural farming technique of letting the weeds grow and mulching heavily around the trees only (using layered branches on the ground for airflow with thick brush on top), and have left enough room around each tree or cluster of trees for the ride-on mower to get around if need be. The trees were watered three times by hand through the first summer – picture a ute with a 1000 litre container on the back and a hose coming out the back – just to keep them alive. Despite this being a low budget project, we did spend good money initially on mostly heritage variety fruit trees such as Arapahoe Red Leaf peaches and Monty’s Surprise apples.

The berry and oolong tea garden has been developed on land left lying fallow for many years. This land had a lot of heavy machinery running over it when the Academy buildings were being built and subsequently the underlying soil was well compacted and poorly drained (it pooled with water in winter). We sought to improve it by having a contractor plough the existing grass and weed cover, rip the soil to improve drainage, contour to eliminate humps and hollows, then finally rotary hoe in a sprinkling of lime and compost.

Soil test results still showed deficiencies in boron, potassium, and phosphate after this treatment, so we applied organiBOR (a BioGro-approved form of boron) and rPr (rock phosphate), rotary hoed it in, then set about planting. The oolong tea was planted in October 2014. Plants have been laid out in a circular pattern (I’m fond of curved shapes in the landscape) which fitted well with the shape of the area. Once we’d added a few gaps here and there we had the makings of a maze and that will be fun for students in the years to come. We also put plant guards around the oolong tea plants (as we did the trees in the food forest), and mulched heavily using the stick and brush method.

One interesting observation was the extent to which the ripping and contouring worked. The soil went from a poorly drained, somewhat soggy area, to a fairly porous, somewhat fluffy soil ready for planting. Hopefully this winter it will be ready.

HORTECOLOGY SANCTUARY, UNITECH, AUCKLAND

Size: 1.5ha (3.7 acres)

Established: 1999

Crops: subtropical fruit trees, vegetables

Climate: some frost in winter, mostly warm and humid

Soil: fertile, free-draining, rocky

Organic vegetable gardens of Unitech with the food forest in the background.

Unitech’s Hortecology Sanctuary is something of a subtropical oasis, evolving over the last 15 years to look and feel like a forest environment. There are white sapote (Casimiroa edulis) trees abundant with fruit. Despite being in the middle of Auckland and prone to frost, frost-tender species such as giant abyssinian bananas also grow, a good example of how pioneering species give protection for frost tender subtropicals to grow later on.

Abyssinian bananas don’t produce fruit, but are great for ‘chopping and dropping’ due to their sheer mass of leaf and the fact they store a lot of water in their biomass. It is not unheard of for people to use abyssinian banana cuttings around the base of fruit trees in dry summers to keep them alive. The soil at the sanctuary is also volcanic so it’s reasonably fertile and free draining, although somewhat rocky. Avocados which grow alongside the white sapote trees would simply not work if the soil wasn’t free draining. There is one downside – due to the prevalence of rock in some places, trees that can’t get their roots down are susceptible to blowing over in strong winds. This happened to a sapote recently, but even though blown over and lying on its side it was still growing and putting out new shoots.

A pathway through the hortecology sanctuary.

In the beginning the sanctuary used the hay bale technique, laying down a thick layer of hay (up to a quarter of a bale thick) to kill off the existing waist-high cover of kikuyu. A lot of acacia were planted as pioneering nitrogen-fixers, which over time have been coppiced and culled as the fruit trees have grown in size. Citrus is prolific at the edges, along with ladyfinger bananas and Jerusalem artichokes, which you better like if you decide to plant them because once planted they are hard to get rid of.

I saw this food forest a few years ago when maintenance had lapsed for several years. It was evident how the trees which were initially closely planted were having a detrimental effect on each other due to crowding and too much competition. Feijoas, although moderately shade-tolerant, were suffering in the understorey due to low light conditions. Since then a lot of trees have been taken out and light gaps are now plentiful, creating an ideal environment for the planting of more subtropicals.

USING DECIDUOUS FRUIT TREES IN A FOOD FOREST

Cow parsley.

Deciduous fruit trees have been used extensively in the Waihi food forest. You need to be sensitive to the location of deciduous fruit trees. They like good airflow to help reduce the incidence of disease, especially in humid areas so groundcover shrubs taller than 1m underneath are inadvisable (so as to not restrict airflow).

Companion plants like buckwheat and cow parsley work well under deciduous fruit trees. At the BHU (Biological Husbandry Unit) at Lincoln University, cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris) planted in large swards under the apple trees greatly reduced the incidence of black spot (the fungal spores that had overwintered on mummified fruits couldn’t get themselves up and out of the cow parsley come spring).

Buckwheat in turn halved the incidence of leafroller caterpillars when planted under apple trees at another site in Canterbury. Deciduous trees are often better placed at the edges where they’ll receive maximum airflow, with evergreen trees further in. Citrus trees also work well at the edges where they’ll get plenty of sun, however keep them away from cold prevailing winds which they resent being exposed to.

Buckwheat under-planted in an orchard.

KELMARNA GARDENS, AUCKLAND

Size: 0.8ha (2 acres)

Established: 1981

Crops: subtropical fruit trees, vegetables

Climate: warm and humid

Soil: heavy clay soil

Harvesting veges at Kelmarna Gardens.

Most of the work I do is in rural areas but this is another example of a food forest in Grey Lynn, just minutes from the centre of Auckland City. The reason I’m fond of this particular example is (in part) because it’s a small oasis in one of the most expensive suburbs in NZ, and it’s surrounded by paddocks and grazing cattle. It’s also open to the public and adeptly shows what is possible in a smaller area.

Ross Kesby of Kelmarna Gardens, with helpers Esther and James.

Kelmarna Gardens scrambles and winds its way across its site, intermingling vegetable gardens, chooks, compost areas, glasshouses, and various small buildings. It contains an abundance of subtropical species including bananas, white sapote and avocados, persimmon, citrus, and a scattering of deciduous fruit trees. The approach by the gardeners at Kelmarna is to concentrate on species that aren’t overly affected by fungal diseases which can be prolific in this humid climate. Banana and white sapote are two fruit trees that are almost trouble-free, and banana plants gobble up organic matter with gusto. Once a main stem (banana) has fruited, you simply cut the bunch off once the fruit has started to turn yellow and bring the bunch inside to ripen (otherwise the birds will likely beat you to it).

A banana jungle.

You then cut the spent stem down to near ground level in order for the next one to grow up and flower/fruit. There is almost always a baby stem growing up from an underground corm, just waiting to emerge. Bananas also need a reasonable amount of water for the fruit to adequately swell. In a smaller scale food forest like Kelmarna there are good opportunities for layering because there are lots of edges which receive sunlight. Citrus do well at the edges, but so do feijoa, figs, loquat, guava, bananas, and nearly any kind of smaller fruiting tree.

In many places at Kelmarna you can see very simple plant guilds (positive plant associations) such as deciduous fruit trees with comfrey underneath. The fruit trees at Kelmarna are also pruned to restrict their overall height and make harvesting easier.

Kelmarna has such a heavy clay soil that if you dig a deep hole in winter it will start to fill up with water as it seeps in from the surrounding sodden soil. The gardeners dealt with this by creating mounds to plant into, and by applying very thick mulch, in effect building the soil over time. Mulch slowly breaks down, and worms draw this organic matter down through and into the clay soil, improving drainage and structure. Also by keeping trees pruned and small, the root system does not dive too deeply into the soil.

A large chicken run is part of the food forest.There are many different approaches to creating a food forest, but don’t expect it to be a trouble-free ride. However, with adequate research and assistance there is no reason you cannot have your avocado or peach and eat it too.

Love this story? Subscribe now!

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.

This article first appeared in NZ Lifestyle Block Magazine.