3 coastal spectacles around New Zealand to visit this summer

Sea stacks, limestone arches and caves are not a random quirk of nature but a result of New Zealand’s unique and complex geological history.

Words and photos: Extract from Mountains, Volcanoes, Coasts and Caves by Bruce W. Hayward

One-hundred of New Zealand’s most outstanding natural landforms and geological sites are highlighted in Mountains, Volcanoes, Coasts and Caves: Origins of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Natural Wonders. Bruce W. Hayward explains, in relatively simple terms, how each was formed and may have been moulded into the spectacle we see today. When taken together, the accounts of all these sites tell the story of the 500-million-year history of New Zealand and our small, mostly submerged, continent of Zealandia.

Here are three coastal wonders to put on your bucket list this summer:

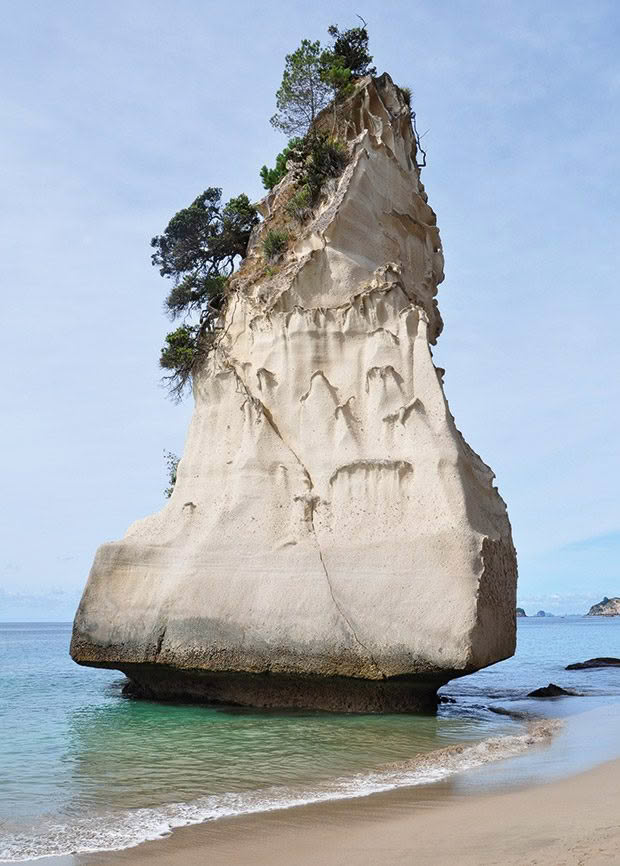

Cathedral Cove, Coromandel Peninsula

Iconic Gothic Arch eroded through volcanic ignimbrite cliffs.

View to the north over Cathedral Cove. Photo: Alastair Jamieson.

Cathedral Cove with its sea arch is the centrepiece of Whanganui-a-Hei (Cathedral Cove) Marine Reserve, which stretches along the coast for 4 km north of Hahei. The cliffs of this section of coastline are composed of ignimbrite rock that was erupted out of the Whitianga Caldera about 8 Myr ago. The Whitianga Caldera is a 12-km-diameter giant crater that collapsed into an emptying shallow magma chamber as the hot pyroclastic flows and ash were violently erupted.

The pyroclastic flow of extremely hot volcanic glass, pumice, crystals and gas cooled and solidified to form the ignimbrite rock we see at Cathedral Cove. The caldera, which stretches from Whitianga Harbour across to Hahei and the north end of Hot Water Beach, was a smaller version of the large Rotorua and Taupō caldera craters.

The iconic sea arch at Cathedral Cove has been eroded along a near-vertical fracture plane (visible in the apex of the V-shaped roof) through the massive ignimbrite rock. Its Gothic Arch profile is the basis for the name of this internationally famous tourist attraction.

Following the ignimbrite eruptions and caldera formation, degassed viscous rhyolite magma squeezed up along at least eight different subterranean conduits or pipes and was extruded as rhyolite domes into the crater. Each dome is surrounded or separated from the others by the earlier erupted ignimbrite. These eroded domes form the hills between Whitianga Harbour and Hahei.

The ignimbrite that we see along the coast is cut by a few widely spaced near-vertical fracture planes. In the last 7500 years, since sea level reached its present height after the low sea level of the Last Ice Age, storm waves have managed to erode along some of these fractures and then widen them out to sizeable caves. One of these is the 20-m-wide, 15-m-high sea arch that passes right through a short promontory in the middle of Cathedral Cove (22.1). The vertical fracture can still be seen above the ‘V’ at the apex of the cave’s ceiling.

Aerial view to the south of Cathedral Cove’s sea arch and the larger sea stack that have been eroded by wave action out of the ignimbrite rock over the last 7500 years or so. Photo: Alastair Jamieson.

Elsewhere along the coast around Hahei there are a number of other sea caves and arches that can be entered in a small boat or kayak when the sea is calm. The waves entering these caves compress the air, which may blast out the fractured rock along the joint plane. By this process the backs of several caves have been eroded upwards to the top of the cliffs creating an arch and ‘blowhole’ that smaller tourist boats will explore.

Best seen from: There are panoramic views of the coast and islands of Mercury Bay from the lookout at the end of Grange Rd, Hahei. Walk or catch the shuttle bus up the hill from Hahei to the lookout and start of Cathedral Cove Walkway. Alternatively take a tour boat ride or water taxi from Whitianga for views of this embayed coastline or hire a kayak from Hahei and paddle there.

Take a closer look: Take the Cathedral Cove Walkway from the end of Grange Rd along the cliff top and down to the beach (30 mins each way).

Mōhakatino coast, North Taranaki

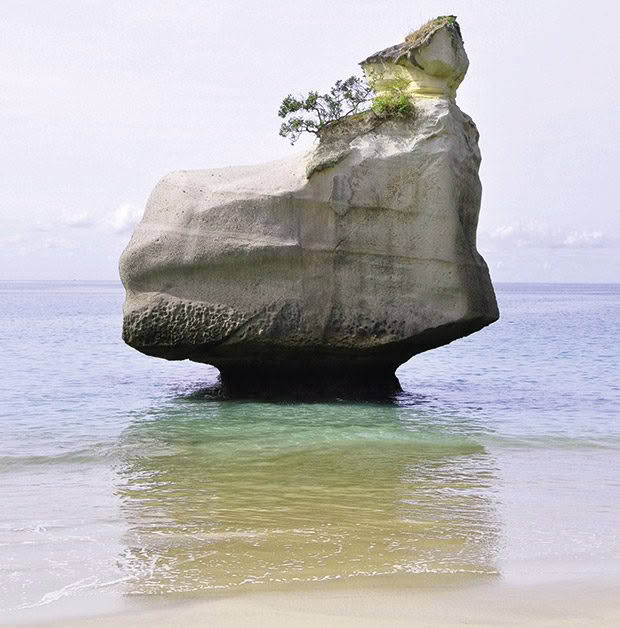

A plethora of sea stacks, caves and arches ash and peat

Part of the coast south of the mouth of the Mōhakatino River with three sea stacks and numerous sea caves and tunnels in the cliffs behind. The orange strata forming the upper part of the cliff are beach and dune sands deposited during the Last Interglacial period of high sea level, 130–120 kyr ago. Photo: Alastair Jamieson.

The coastline south of the Mōhakatino River mouth is one of two places in North Taranaki where there are sensational sea caves, arches and stacks eroding out of the relatively soft cliffs. The other, better-known, locality is south of the mouth of the Tongapōrutu River. In both places the cliffs are eroding back quite rapidly into muddy fine sandstone and mudstone that was deposited 11–9 Myr ago (late Miocene) on the seafloor at deep bathyal depths (about 1000 m). These layered strata are tilted gently to the southwest and get progressively younger as you walk south along the coast.

The rocks are cut by steep faults and joint planes, many of which are aligned southwest–northeast. When the tide is high, breaking waves slam into the base of the cliffs, forcibly injecting water along these planes of weakness. Over time caves are eroded into the cliffs, sometimes extending right through a small point to create a sea arch. Further erosion widens the arch, extending it upwards until the roof collapses in. This creates a sea stack, usually separated from the cliffs by beach sand. Continued erosion around the base of the sea stacks makes them more precarious until they finally fall over and are removed by the waves.

A 12-m-high, narrow sea stack viewed through an arch on the was being eroded by the sea. Photo: Alastair Jamieson.

Because of thisrapid erosion, few sea stacks along the North Taranaki coast would be more than 100 years old. The Mōhakatino cliffs and stacks are about 20 m high, and the fresh grey Miocene sedimentary rocks are commonly capped with more weathered orange-coloured sand, volcanic and peat.

These younger sediments were deposited on top of a shore platform that had been eroded intertidally by the sea into the underlying strata during the Last Interglacial period, 130–120 kyr ago. Since then, North Taranaki has slowly risen at about 20 cm per 1000 years. As a result, the former intertidal platform now forms an uplifted terrace on top of the cliffs, 15–25 m high above the beach. Its undulating surface is due to old sand dunes deposited on top of the shore platform.

Dozens of sea stacks, caves and arches occur along the Mōhakatino coast, North Taranaki. They are eroded out of mudstone and muddy sandstone layers that were deposited on the seafloor during the late Miocene, about 10 Myr ago.

State Highway 3 between Awakino and Tongapōrutu runs along this narrow coastal terrace between the modern cliffs on the seaward side and the steep slopes of the uplifted 120-kyrold cliffs on the landward side.

Take a closer look: From the Mōhakatino River bridge on SH 3, walk 400 m down to the open coast on the south side of the river (only accessible for 2 hrs either side of low tide). Sea caves, arches and stacks are present down the coast for 3 km. Make sure you return before the tide cuts you off.

Tunnel Beach (Dunedin)

New Zealand’s widest sandstone sea arch

View north up the coast from the Tunnel Beach access track. The magnificent sea arch is cut through part of the small finger-like peninsula. The three rock stacks are also made of sandstone and probably were formed when similar sea arches collapsed, separating them from the adjacent cliffs.

The widest sandstone sea arch in New Zealand can be seen in the cliffs at Tunnel Beach on the southern outskirts of Dunedin city. It is quite unusual for a New Zealand sea arch, because it has been eroded through massive calcareous sandstone rather than the more common arches in limestone, ignimbrite or other volcanic rock types.

This sandstone (Caversham Sandstone) was deposited on the seafloor in shallow water, about 50 m deep, during the early Miocene about 20–16 Myr ago. The sandstone is grey-white when fresh, but weathers to a yellowy-orange colour where erosion is not rapid. It is a mix of quartz grains and 40–70% lime, which has helped cement the sand grains together into a calcareous sandstone or sandy limestone. Rare fossil lampshells, sea urchins and even rarer whale bones have been found in the sandstone.

When the tide is full the sea reaches all the way to the base of the sandstone cliffs at Tunnel Beach (to the right of the small sea-arch peninsula). The public access track wends its way down the slope and disappears into a manmade tunnel. The cliffs and most of the slopes are composed of sandstone, capped near the top of the slope by weathered basalt lava flows of the Dunedin Volcano. Photo: Lloyd Homer, GNS Science, 29605.

Caversham Sandstone underlies all of the Dunedin Volcano, but is mostly seen at the surface and in the sea cliffs on the northern and southwestern outskirts of Dunedin city. Just south of Dunedin the sea cliffs are composed of an uplifted, eroding block of Caversham Sandstone. On either side of Tunnel Beach, these sandstone cliffs and steep slopes are overlain with slight erosional unconformity by weathered basalt lava flows from the Dunedin Volcano (87.3). Some of the volcano’s fresh, columnar-jointed basalt lava flows are down-faulted to sea level and form the cliffs at either end of the Tunnel Beach sandstone block at St Clair and Black Head.

This dramatic 20-m-wide sea arch has been carved by the waves along vertical joints through 20-Myr-old sandstone at Tunnel Beach, south of Dunedin.

The sandstone exhibits weak layering (bedding) and is cut by a number of near-vertical, widely spaced joint planes. These joints are zones of weakness in the rock, and the breaking waves exploit them by blasting out the sandstone, grain by grain, as they erode their way along the fractures. This erosion has created numerous guts, sea caves, pinnacles and the dramatic sea arch at Tunnel Beach.

Best seen from: View from the Tunnel Beach Walking Track (10 mins) off Blackhead Rd, or explore the beach and sea caves at low tide (40-min. return).

Mountains, Volcanoes, Coasts and Caves: Origins of Aotearoa New Zealand’s Natural Wonders by Bruce W. Hayward, with aerial photography by Alastair Jamieson and Lloyd Homer, Auckland University Press, RRP $69.99.